The 1970s were the early days of the Asian American movement. Spurred by the regrowth of Asian immigration — thanks to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 — an educated, empowered Asian American youth supported the growth of grassroots social, political and creative activism among the population. Passionate attempts at a Pan-Asian collective spirit arose on campuses and in Chinatowns across the country. A handful of key political, social and artistic organizations formed, including Asian Americans Advancing Justice, I Wor Kuen, Kearny Street Workshop and Basement Workshop. Fast forward to 2023, and Asian American youth today are retracing, rereading and rediscovering the ripple effects of their predecessors’ actions in the 1970s.

In a Chinatown that resembles the living ghost of 50 years past, 26 year old director Connor Sen Warnick sits for tea with fellow Chinatown resident, Eleanor Yung. Eleanor is a dancer, choreographer, community organizer and one of the founding members of Basement Workshop, as well as an upcoming cast member of Characters Disappearing, Connor’s debut feature film, which wrapped at the end of 2022.

In Characters Disappearing, cousins Chris, played by Connor, and Mei, played by Yuka Murakami, confront the sudden disappearance of their grandfather, Gong Gong. As they care for their now-widowed grandmother, played by Eleanor, more people around them begin to vanish. The protagonists navigate a changing, confrontational city plagued by persistent looming danger as the film merges past with present. In an emotional rhythm, it oscillates between themes of collective paranoia, the complexity of identity, and grief.

Below, FAR–NEAR discusses the political, historical and cultural context of the film with Warnick and Yung.

Mei and her best friend, Lu, portrayed by Yuka Murakami (left) and Von Hyin Kolk (right).

Lulu Yao Gioiello Connor, what drove you to create your upcoming film, Characters Disappearing? Can you talk a little bit about what it’s about and what inspired the story?

Connor Sen Warnick The story primarily follows three characters in their early 20s going through a difficult stretch in their lives. These characters are Mei, her cousin Chris and her partner Leonard. As the movie unfolds, they are each forced to reckon with loneliness, loss and paranoia in relation to their complicated identities and communities. In building this world, I transposed a significant amount of my own personal history within a historic context that spoke to me. Between these three protagonists, as well as the constellation of polyracial characters who surround them, the film explores the nature of relationships that bridge across layers of race, class, culture and age. What people will see on screen is a blend of my own experiences as a Chinese American New Yorker with stories I gathered through interviews with Chinatown elders. Many of them also appear in the film as supporting characters or background extras.

Lulu What made you decide to produce and film the project in 2022?

Connor My close friends and I — and the larger AAPI community — experienced a lot of pain, violence and danger in the last few years. This film has been an opportunity for catharsis. As a filmmaker, I am motivated to create more authentic, multifaceted and formally rigorous depictions of AAPI experiences in cinema. One hope is for this film to generate more support for AAPI independent films so that we can dispel the marginalization and stereotyping of our community.

My team and I also wanted to prove that a film of this ambition — a quasi-period film, shot on 16mm, with over a hundred characters and twenty-some locations — could be produced with a budget this sparse. It was the first feature length endeavor for most of us and we needed to pull off miracles together on a regular basis to make it possible.

When you go through the grueling process of making a movie it almost trauma-bonds you together for life. My wish is for this project to open doors, professionally and artistically, for everyone who worked on it. It’s beautiful to see how the production has turned into a loving community.

I am forever grateful for everyone’s heroic efforts. We are proud knowing that the urgent conditions under which the film was produced have translated into the emotion of the images.

A toast to Mei’s new apartment.

Lulu Why does it take place in the 1970s? What’s the significance of the political and cultural communities of the Asian American movement to your film?

Connor In the summer of 2021, during the pandemic and amidst a disturbing spike in violence against Asians (in particular, the Atlanta spa mass shooting), I was feeling very afraid and depressed. In search of something to feel hopeful about, I dove into pockets of AAPI activism that had previously been blindspots for me. It was a way to see how others had combatted hatred, injustice and discrimination. I read what I could about grassroots activist groups like the I Wor Kuen and Basement Workshop. Learning about the impact that they had during the 1970s in NYC made me want to do more for my own community. I thought I could use my voice as an artist to bring their legacy to the forefront today at a time when it felt needed. I wished I had learned about them earlier.

Although I had been developing the characters and story before this, the more I discovered about the 1970s Asian American movement, the more I wanted to place a film within that time. The eras are full of parallels beyond the political context: basketball, art and poetry continue to be pillars of Asian American subculture. The elders I spoke with confirmed this connection.

With that said, I don’t want to misdescribe the film as being fully “set” in 1971. Characters Disappearing exists in a world that’s suggestive of both Chinatown’s past and present. My intention was to make something of its own unique and timeless design, that would be able to communicate with future viewers and ones that lived through that past. To achieve this, the precision of the emotional rhythm between the images and the sounds took precedence over historical accuracy.

Leonard walking through a Chinatown night exterior, portrayed by Dylan Breaux.

“We must respect the people who paved the way for us, who helped shape the world we occupy, whether we’re aware of the full extent of their impact or not. With this film, I want to show love and fidelity to honor all the elders who were generous enough to share their experiences with me.”

Chris and Popo in Columbus Park, portrayed by Connor Sen Warnick (left) and Eleanor Yung (right).

Lulu Who is Eleanor Yung? How did you two meet and how did she end up acting in the film?

Connor I was connected with Eleanor by her husband, Bob Lee, who was a member of both the I Wor Kuen and Basement Workshop in the early 1970s before founding the Asian American Arts Centre. From October 2021 to May 2022, as I developed the screenplay for Characters Disappearing, I was searching for as many firsthand accounts from surviving 1970s Chinatown activists as I could find. Within moments of meeting Eleanor, I thought to myself that she would be perfect for the role of Popo, the grandmother of Characters Disappearing’s two main protagonists, Chris and Mei. Eleanor has a grace, calmness and clarity within her spirit that is instantly recognizable. I can’t imagine anyone else playing Popo. The more she told me about herself and her past as an activist, dancer, choreographer and practitioner of Eastern medicine, the more evident it became that everything about her aligned harmoniously with the film’s story and its themes.

Lulu As part of today’s younger generation, what do you look for in older generations?

Connor I mostly look to my elders for friendship and perspective. I’m curious about how individuals change and evolve based on time and place. When I think about the young people around me, I often wonder what kind of old people they will become. So, I look for those older than me to be generous with their knowledge, but I’m also sympathetic to the ones who are protective of it.

This preoccupation manifests in the form of Chris, the character I play in Characters Disappearing. After his grandfather’s disappearance, Chris obsesses over a story about his great-grandfather’s relationship with a 250-year-old monk. Chris begins practicing the monk’s longevity methods, which ends up doing severe damage to both his health and relationships.

We must respect the people who paved the way for us, who helped shape the world we occupy, whether we’re aware of the full extent of their impact or not. With this film, I want to show love and fidelity to honor all the elders who were generous enough to share their experiences with me.

However, it’s important that I make clear that my intention is not for the film to reenact their stories, though their perspectives inform the setting and climate of this fictional story. I would like to package their accounts into a supplementary project someday — perhaps a book, or an online project, or an installation.

People like Eleanor, Bob, Danny, Virgo Lee, Corky Lee and Arlan Huang inspired me to learn more about the complex history of Asians in New York and bridge my understanding of the past with my understanding of the present. I hope not only to preserve and crystalize in some way their spirit, but also to advance the example they set for my own generation and others in the future.

Mei and the IWK. Left to right: Peter Ding, Derek Zheng, Yuka Murakami, Erin Malimban and Khang Pham.

Lulu Living in the West, we’ve developed these hybrid identities that take from our cultural backgrounds and the society we live in. In a place that leaves a lot of us valuing and fending for ourselves as opposed to the community, how does a person ethically participate in collaboration?

Connor Making films is a good example of what’s possible when collaboration is effective, but it’s quite difficult to sustain for a long period of time. By the end of our shoot, we were all well past our limits. Still, when it works out there’s truly nothing like it. On our set, I always tried to give my crew the freedom to make their own decisions and the space to take risks. A good leader should know when to follow. We were very short on time and resources, but I felt this necessitated a more flexible, freewheeling approach rather than a restrictive one, so long as the boundaries were understood by all.

My belief is that the more true you can remain to yourself and your own experience, the more energy and connection you can create with others in your community, but that must start with the individual. Even in the context of a collective, I believe one should always be skeptical of the shared will of a larger group. This is a central theme in the life of Mei, the protagonist of Characters Disappearing. Mei leads the I Wor Kuen (IWK), a radical leftwing Marxist-Maoist Chinatown collective that was active from 1968 to 1975. Her faith in the IWK’s philosophy is greatly tested, not only by repressive forces, but by internal disagreements. The film examines this inner conflict. She’s young and idealistic but is growing weary. She questions whether the people she’s aligned with still believe what she does, and whether the personal sacrifices made for the cause have been worth it. This reflects the impasse that the IWK was really dealing with as a group in late 1971.

A solo dance by Popo to honor the passing of Gong Gong. Choreographed by Eleanor Yung.

Lulu Eleanor, what was your first impression of Connor and how did you end up as part of Characters Disappearing?

Eleanor I got a call from Connor who wanted to meet up. The soft-spoken young man talked about his project and asked about Basement Workshop and the Asian American movement of that time. Later he sent me a link to his earlier work, Late By Any Clock, and asked whether I would be in his next film, Characters Disappearing. After watching his previous film, I realized that in his minimalist style, his art carries layers of meanings. Rough around the edges and literally dark, it’s raw but not abrasive. I am not a film critic, but I was reminded of Wayne Wang whom I met in the early ‘70s before Chan Is Missing. I thought it was serendipity that Connor wanted to do a film about the time when I was his age.

When I founded the Asian American Dance Theatre in 1974 (later renamed to the Asian American Arts Centre), Bob and I wanted to help create a better world for our daughter. We created art programs for the community. And here comes Connor, of the younger generation, wanting to bring more attention to Asian Americans. How could I not help and be a part of it?

Attendees of an IWK-hosted screening of The East is Red (1965). Left to right: Prominent NY-based Asian film critics Phoebe Chen and Kristen Yonsoo Kim, Chinese artist Lu Zhang and her husband Herb Tam, Director of Exhibitions at the Museum of Chinese in America, Virgo Lee, one of the IWK’s founding members, and Noeva Wong, a lifelong Chinatown resident and activist since the 1960s.

“Asian American youths flocked to Basement Workshop with new ideas, new directions, new projects, making new friends and even life long partners. It was inspiring. Many seeds were sown into fertile soil, from programs for the immediate Chinatown community to network building across the country.”

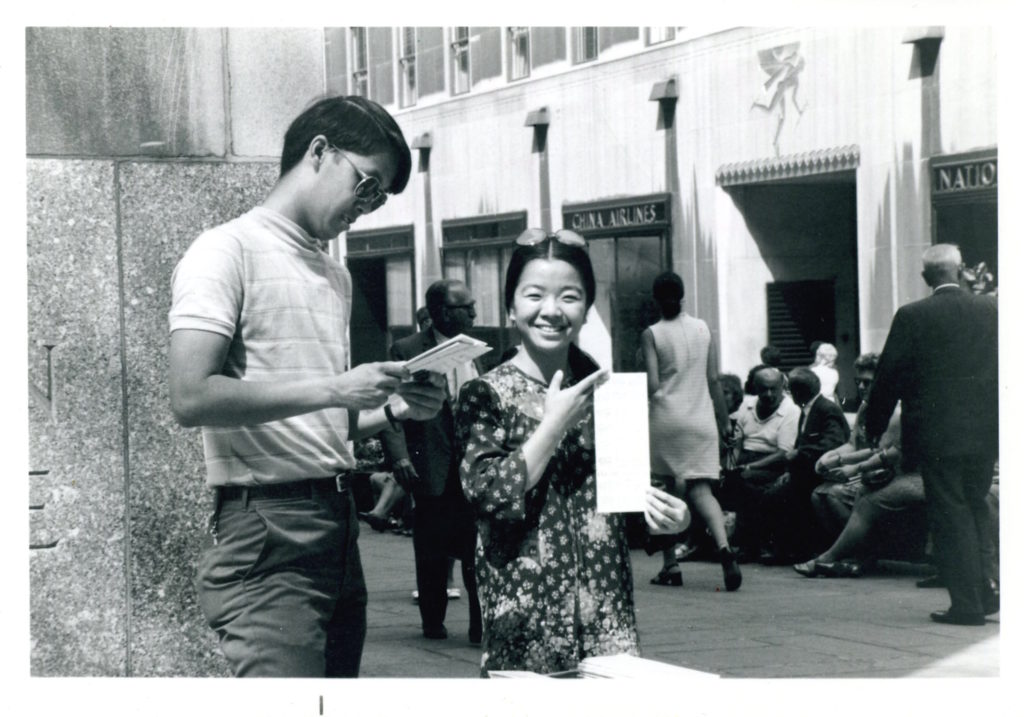

Eleanor leafleting in midtown to promote “Eat in Chinatown”. Estimated around 1970.

Lulu Can you tell me a little bit about Basement Workshop, the organization you helped found?

Eleanor Basement Workshop began in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, towards the end of the Civil Rights Movement. On campus, students were fighting to establish Third World Studies and self-determination. At the time, Black Studies didn’t even exist. That’s where the country was when we founded the Basement Workshop.

Both my brother Danny and I graduated from UC Berkeley, the hotbed of student protests. We had our share of the mid to late ‘60s campus culture. My brother’s Master’s thesis at Columbia University was about NY Chinatown’s urban landscape and its demographic, something that had never been studied before. Chinatown was an excluded enclave of an inner city ghetto. After the passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, there was a large influx of Chinese immigrants moving to the San Francisco and New York Chinatowns. Danny believed that if you had data, you had information you could use to pressure the government to establish public programs. Danny mobilized bilingual Chinese American university students to go door to door to interview Chinatown residents and make site evaluations. Corky Lee was one of the eight on the team. The 1969 Chinatown Study was completed in line with the 1970 Census collection.

When Danny began renting a basement at 54 Elizabeth Street in early 1970, we not only had a physical space where people could meet and hangout, talk, discuss and argue, we also had a creative space that could act like a blank canvas. Danny welcomed everyone to create on this blank canvas. Anything was possible and every idea was encouraged. It was then that Basement Workshop became a hub for young Asian American youths and their energy to converge and flourish.

Danny believed that materials gathered from the community should stay in and benefit the community. He believed in creative planning and programming for all Asians in America. He initiated Bridge Magazine to disseminate information and the building of networks across the country to strengthen communities. With knowledge and creativity, people can grow their programs.

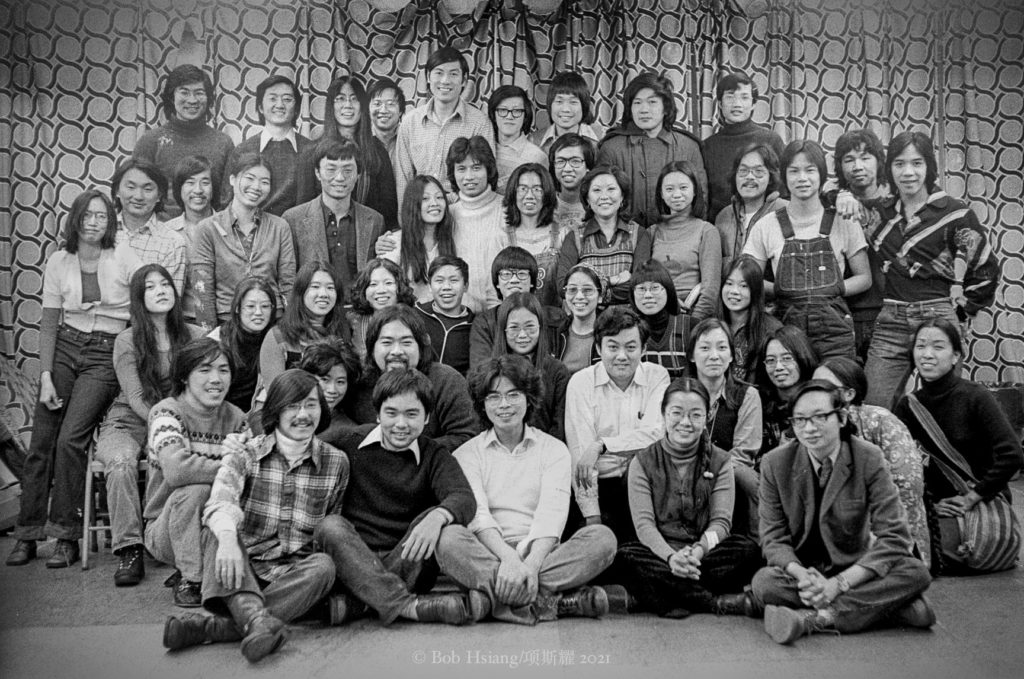

Asian American youths flocked to BW with new ideas, new directions, new projects, making new friends and even life long partners. It was inspiring. Many seeds were sown into fertile soil, from programs for the immediate Chinatown community to network building across the country. It was a robust and creative time albeit with ideological differences and political agendas. It was a significant period when Asian American activism was just becoming its full potential.

In late 1970, we incorporated Basement Workshop with the NYS Department of Law, and in 1971, we acquired a non-profit tax-exempt status from the IRS. BW began applying and receiving grants and donations while growing its many programs.

Basement Workshop on 22 Catherine Street. Photograph by Bob Hsiang, 1972.

Lulu How has our environment changed? Have people changed in the last 50 years?

Eleanor 50 years ago, people in Chinatown wanted to preserve the memories of their lives from their motherland. But with technology and easy access to global travel, Chinatown has been changing quickly. I’d say it’s now comparable to cities in Asia. Those uprooted — the immigrants — want to preserve, while those born and raised in Chinatown are immersed in the living culture; they’re moving forward.

Our environment has changed drastically in the last 50 years. With technology, our context has become global, which makes it ever more important to stay rooted in our tradition. Traditions are not stagnant, they are being lived as they transform and evolve. Preservation of traditions is for museums. In communities, we live our tradition. It is part of us. Tradition is our anchor. Anchors, in my mind, are important for people to be whole.

I think some Asian Americans are lost, so they long to be part of a collective. It is part of finding their identity, to belong to some entity. To take a phrase from Stephen Jenkinson, “belonging is a longing.” Whether first or fourth generation, some have lost their grandparents, lost connection to their parents, lost their language and much of their cultural roots. They can’t decide whether they are Asians or Americans and they can’t define what it means to be Asian American.

In the current global environment it is difficult to be idealistic. People are more likely to lose hope. But hope addresses the future. And we need to address the present, and never lose sight of that. There is a lot we must do. We must entrust ourselves to do it.

Chris, Mei and Popo played by Connor, Yuka and Eleanor, respectively.

Lulu What are the advantages and limitations of collective movements? Can the collective survive today?

Eleanor As I understand it, a “collective” is a loose term for people who came together with similar interests. It has no organization per se. It is not established, but an evolving and fluid entity. Loosely, it is like a circle of friends. “Occupy Wall Street” was a collective.

Basement Workshop had internal “collectives.” One of them actually proposed to disband the organization in 1975. In a collective, it is easy to become anonymous, easy to hide and take little responsibility. Likewise, collectives often hold little responsibility towards their members.

I think some collectives are reactions to the establishment. It is a response to oppression. Its limitations can include lack of transparency, leadership, planning. And because of these limitations, they often are short-lived or unproductive.

So I think, in our society of individualism, collectives — although they may serve some purposes — are often inadequate. I have yet to see a long lasting collective able to be productive, deliver what they promise and most importantly, serve its members well.

The full crowd at the IWK Screening.

Lulu What are the older generations looking for in younger generations?

Eleanor I think the younger generations must live a creative life and one that is productive and does no harm. They need to find happiness and always be kind to themselves and others.

They should find their anchor, their tradition, their lineage roots. Study, research and learn your culture, whether that’s through language, philosophy, spirituality, food, a visit to your home country, talking to elders or going back to school. Knowledge is paramount, without which our actions can be foolish and meaningless.

The younger generation should set goals, create projects, build teams, find support, be engaged, have confidence, be focused and determined. Be kind and thrive together.

Please consider contributing to the outstanding production needs of Characters Disappearing.

Film Credits

Writer & Director Connor Sen Warnick Director of Photography Owen Smith-Clark Production Design & Art Direction Bethany Yeap and Sammy Kim Wardrobe Regina Melady Props Master Mariana Sanchez Bueno Producers Joseph Eusebio, Ruby Rose Krakower, Reina Bonta, Oliver Agger 1st Assistant Director Coren Helen-Gitomer 2nd Assistant Director Emily Park Gaffer Alex Hufschmid Key Grip Tristan Oliviera

Connor Sen Warnick, Director of Characters Disappearing

Eleanor Yung, founding member of Basement Workshop and Asian American Dance Theatre

Lulu Yao Gioiello

Ariana King and Lulu Yao Gioiello