Nothing sad or dark is hidden within Walasse Ting’s paintings. They are bright popping pastels of worldly beauty — female figures, flowers, animals — or energetic ink pieces, many depicting Chinese motifs. Despite being painted in New York during some of the city’s most turbulent years, they feel as far from that world as possible. There is a conspicuous disconnect. Across Ting’s canvases there are no urban skylines, no political grievances, and very few men.

“I think he wanted to convey beauty and love. Those were his biggest things. And joie de vivre, like a joy of life,” the artist’s daughter, Mia Ting, told FAR–NEAR in a recent interview.

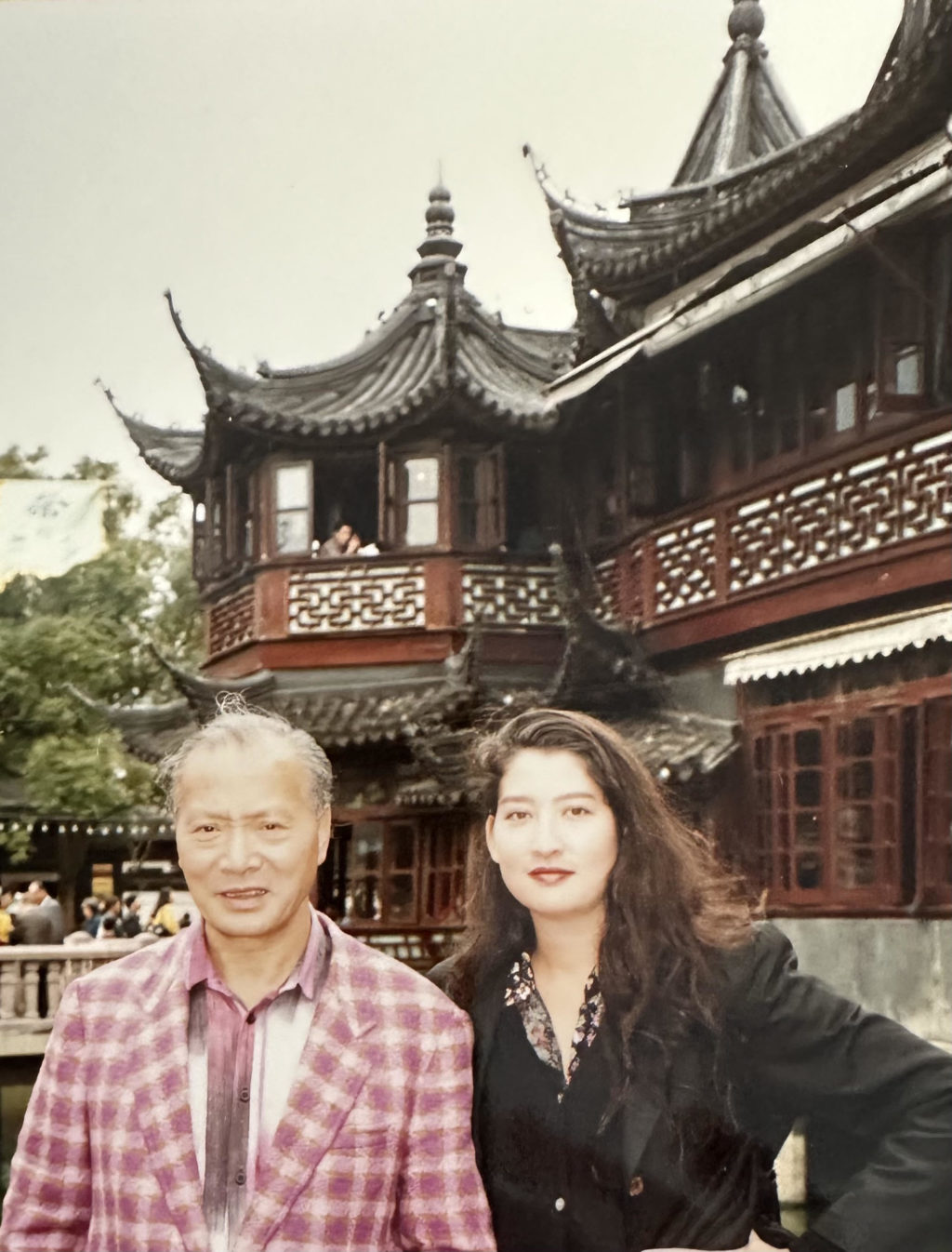

Walasse and his daughter Mia Ting at the Yu Garden in Shanghai, 1988.

Speaking of her father’s intentions as an artist, she added, “It’s like a calling. When you want to be an artist and you want to create, you have to paint. You can’t not paint.”

The works of the late Walasse Ting are currently on display at Alisan Fine Arts, for the gallery’s inaugural exhibition in New York City. Ting maintained a long partnership with the gallery, which was established in 1981 in Hong Kong and has been a pioneer in the art scene for its focus on Chinese diaspora works. The pieces on display in Walasse Ting: New York, New York were all painted in New York between the 1950s and ‘90s; for them to be displayed here and now represents a “homecoming” of sorts for the artist.

Alisan Fine Arts Director Daphne King explained: “When we first started showcasing Walasse in the ‘80s, I think he was better known here in America, and he was already in all these major museum collections.”

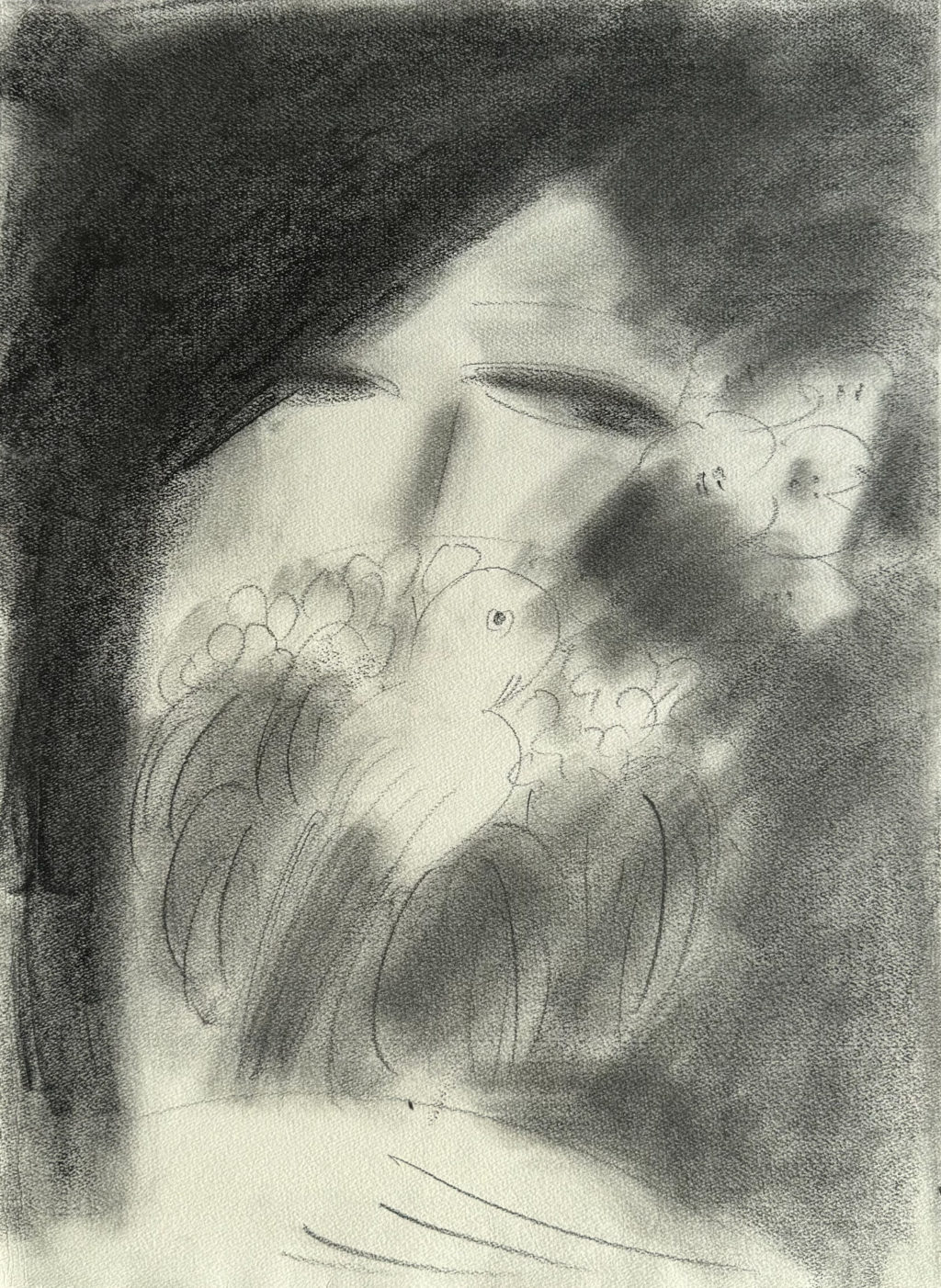

Walasse Ting

Wistfulness, 1990s

Charcoal on Arches paper

44.5 x 33 cm

Courtesy Alisan Fine Arts

King’s mother, Alisan’s founder, wanted to use the gallery’s bridging location in Hong Kong to showcase diaspora artists from China at a time when the country was still mostly closed. Today, however, thanks to the success of his work in Hong Kong and Asian markets, he is better known in Asia than in the city where he first made his mark.

“It’s almost like a turning around, which is kind of ironic because now we brought him back to New York, and I’m realizing here that people actually don’t know him that well,” King said.

Walasse Ting first arrived in New York after a brief time in Paris from Shanghai in the late 1950s when few Mainland Chinese artists were emigrating to the city. As a forerunner in the Overseas Chinese scene, Ting was both a mentor to other diaspora artists, and fully embedded in the New York art world at large.

While most of the pieces in Walasse Ting: New York, New York are paintings, at the gallery entrance is a vitrine containing 1 Cent Life, a collection of drawings, prints and writing published in 1964 by Ting. It features works from Pierre Alechinsky, Sam Francis, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol, among others.

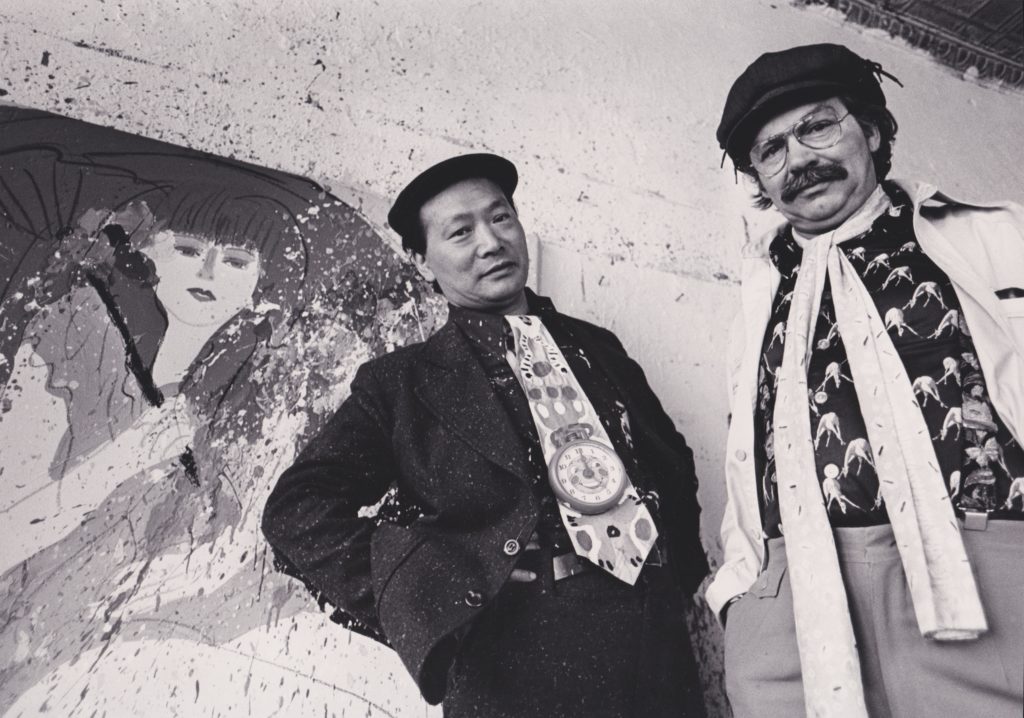

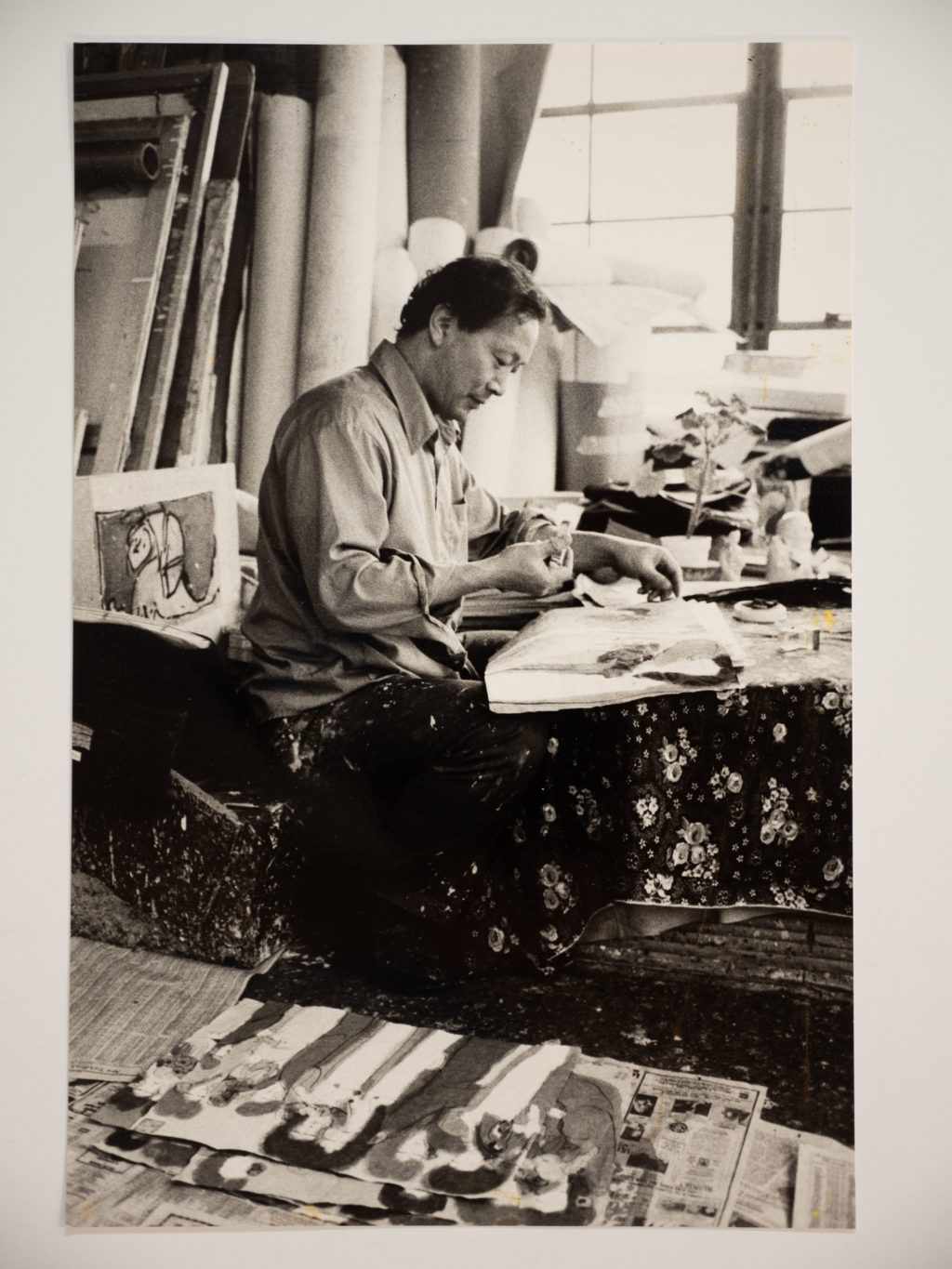

Walasse Ting in his studio, 1980. Photo by Pierre Alechinsky.

“It was also interesting that he had the abstract expressionist artists together with the pop artists. According to my understanding and research, those two groups of artists actually didn’t get along because they were doing different things,” King said. “But I read an article somewhere where somebody said, ‘Oh, it took a Chinaman to put these artists together and work on the project together.’”

In Walasse Ting: New York, New York, the arc of Ting’s body of work shows a nuanced cycling of styles. While his style is consistently uniquely his own, Ting’s mid-career pieces from the 1970s appear to reflect some of the pop influence of his fellow Western contemporaries. In contrast, earlier works of the 1950s and later works of the ‘80s and ‘90s appear to bring more traditional Chinese elements into the subject matter — most notably in the Tang Dynasty-inspired facial features of the women he paints, as well as the recurring animal motifs, such as the horse that appears in numerous pieces.

This shift may or may not be linked to Ting’s own sliding distance from his homeland.

“I think there was always a homesickness,” Mia Ting said. “There were not many Shanghainese restaurants in those days, in the ’70s in New York. And he used to make this thing called ‘Homesick Noodles,’ which were basically like thick, doughy noodles that he put in chicken broth with some spinach because he didn’t have the pickled cabbage or those things. But he was a very sentimental person.” The family was finally allowed to visit China in 1979, and, Ting recalls, he was in “full force” there.

“He could be really sad and melancholic himself, but he didn’t want to show that to the world. He wanted to show what he thought was beautiful in life,” Ting said. “But he used to say he would put that kind of energy into his painting. He wouldn’t show it that way, but he would use that energy to create something positive.”

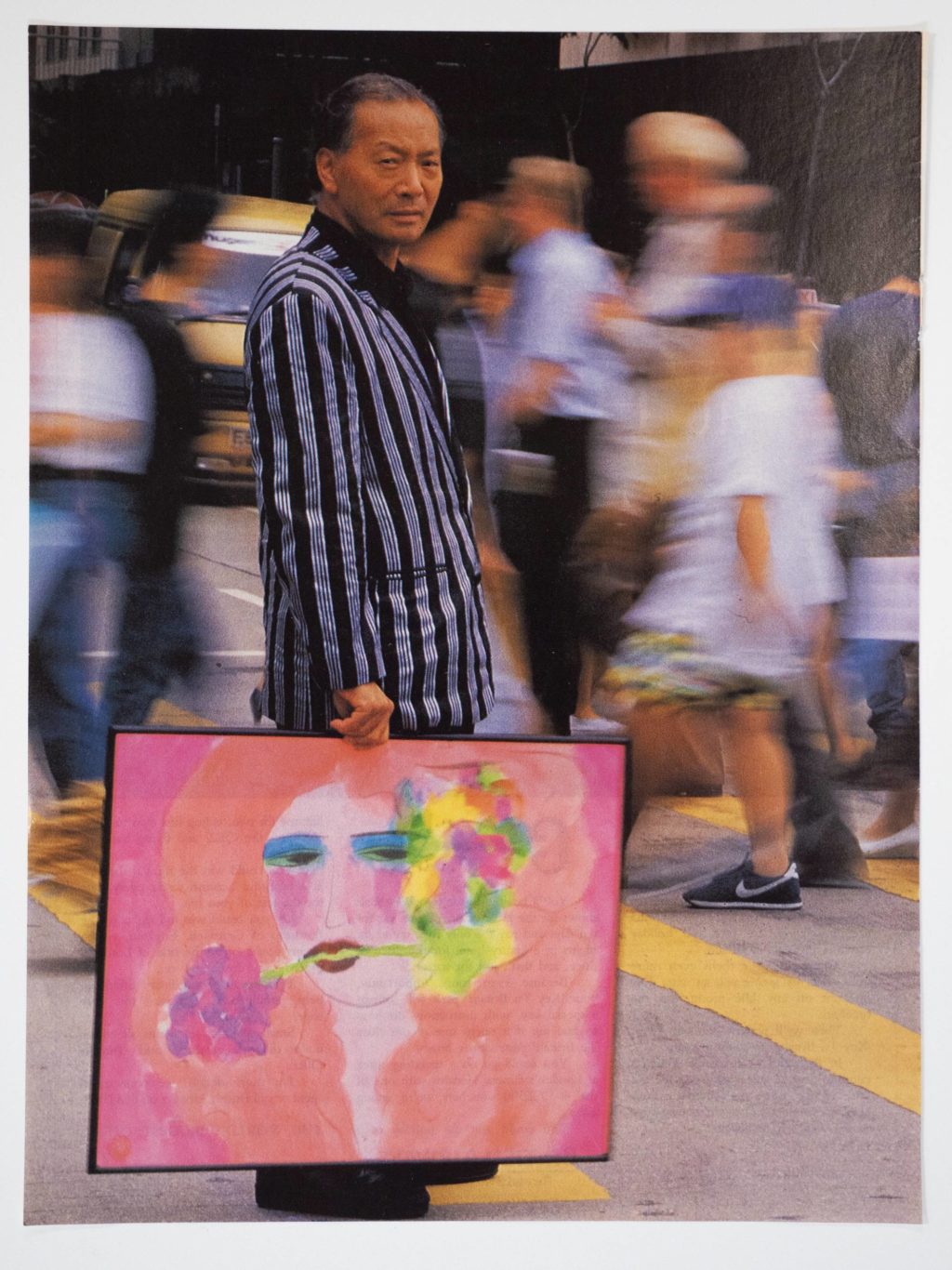

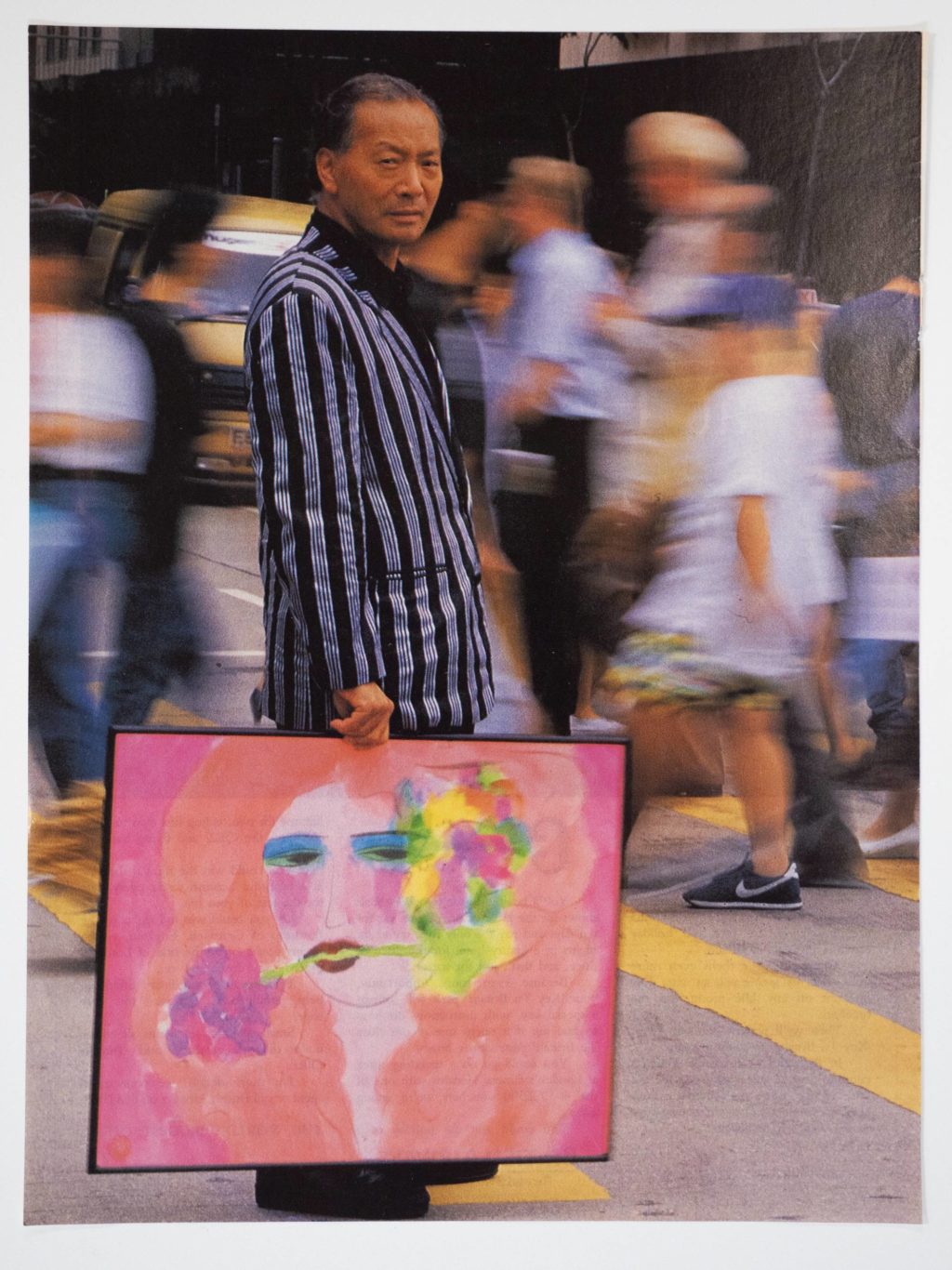

Walasse Ting photographed for Esquire HK, September 1997.

Walasse Ting: New York, New York is open for viewing at Alisan Fine Arts in New York from November 30, 2023–February 16, 2024.