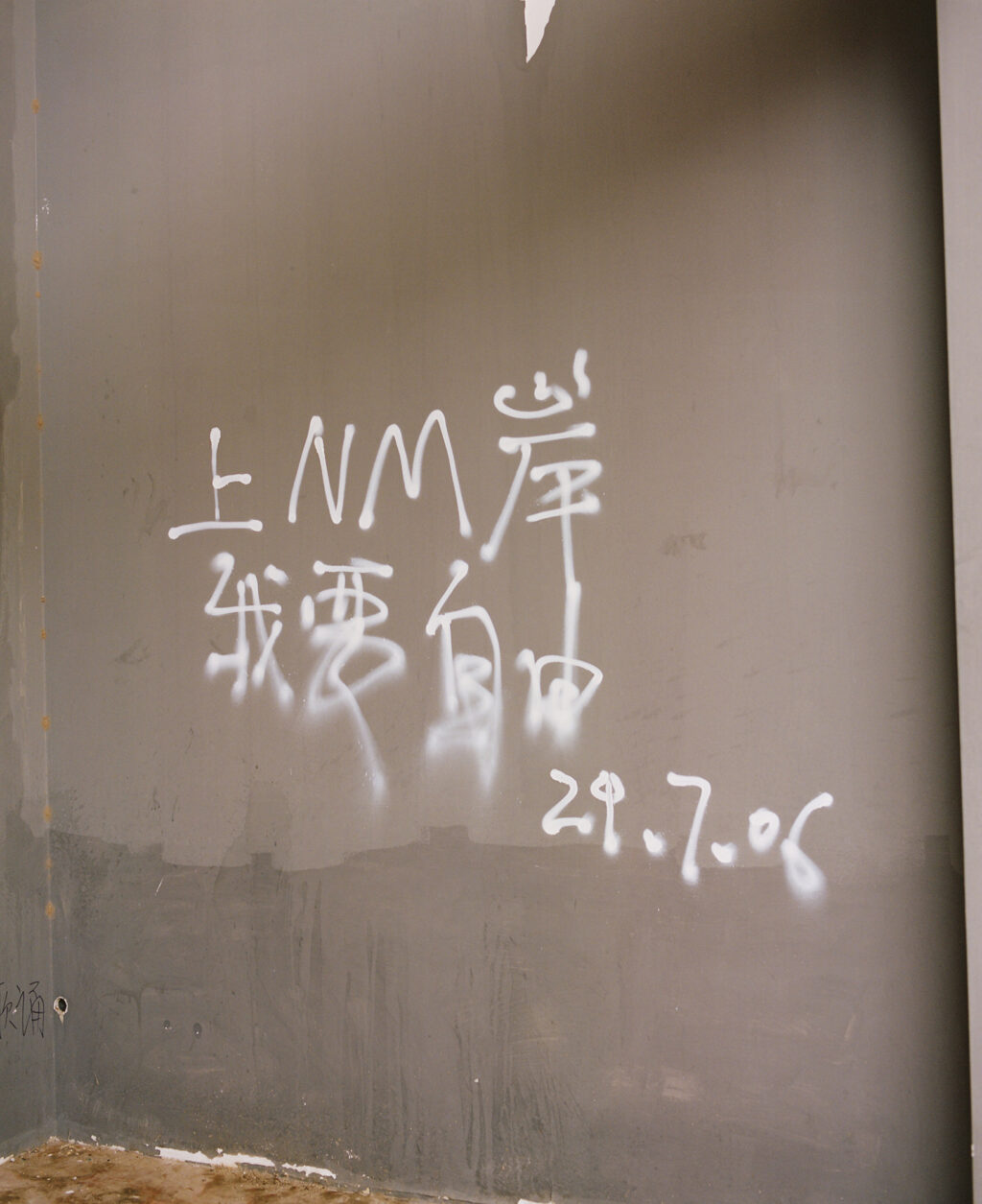

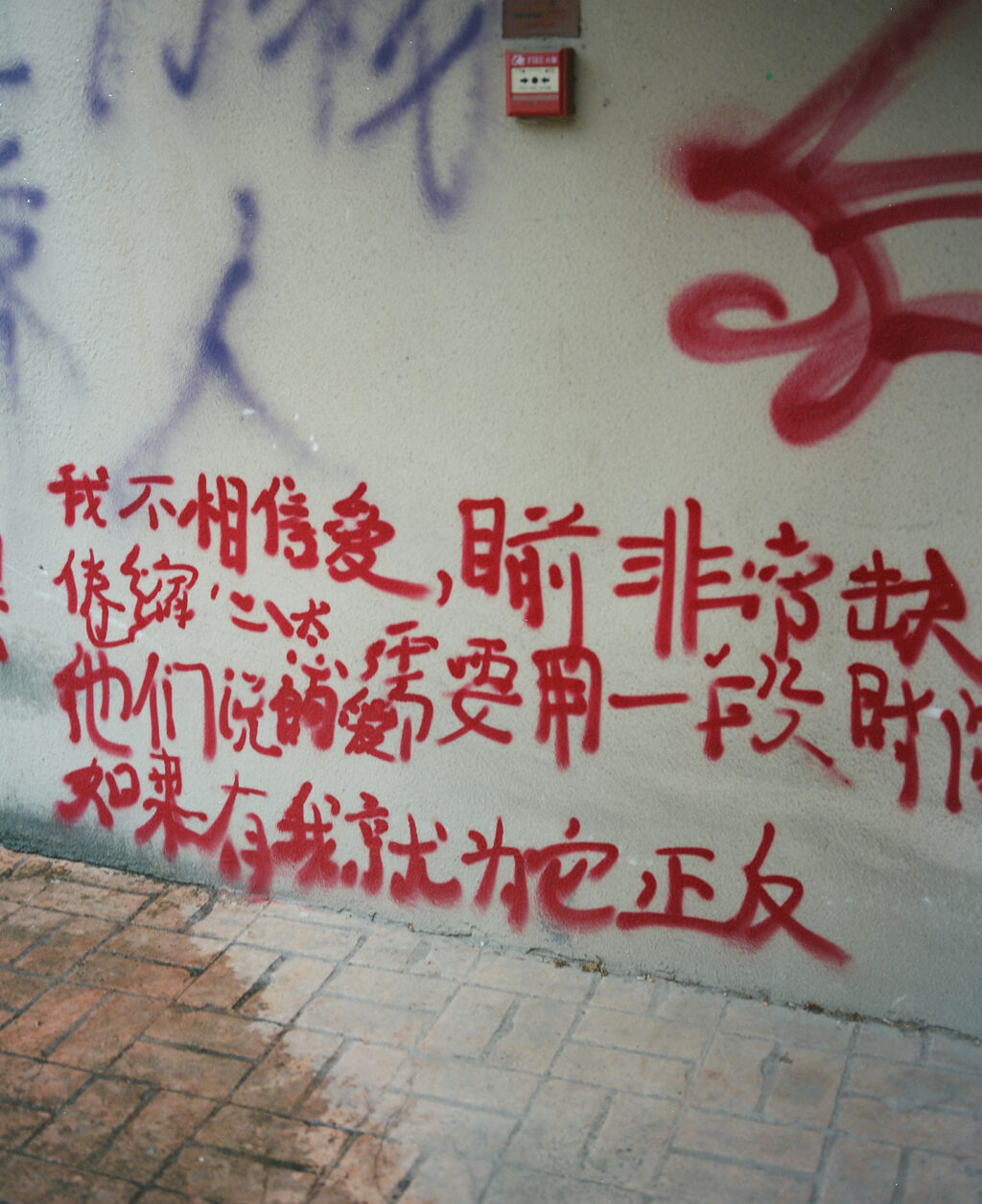

In those years when I returned to Zhengzhou, I often felt a need to wander the streets in search of something — perhaps memories of the past, or simply a sense of familiarity. Dashanghai Shopping Mall became a symbol of that search. Its decline, its dilapidation, its rise and fall — all seemed to mirror my own feelings toward this city. I became enamored by the graffiti in this long-abandoned mall. To me, the writing reflects the inner thoughts and frustrations of the city’s youth — questions about whether “making it” is truly a way out, comments on education inequality and suicide, tangled feelings about love, freedom, ideology.

I grew up in Zhengzhou and didn’t leave the city until I went to university. People often joke about Zhengzhou as being nothing more than “Zheng County,” and to be honest, that’s how I’ve always felt too. If I had to introduce my hometown to someone, I’d probably say it’s quite a boring city. People here try hard to appear otherwise, to seem more interesting — but somehow, there’s a cycle they can never quite break, both externally and internally. Zhengzhou is a city shaped by railways. Unlike other cities in Henan, such as Luoyang or Kaifeng — both ancient capitals — Zhengzhou doesn’t have the same kind of deep historical roots to lean on. It is known as the national hub for rail transport: railways running north–south and east–west all converge here. People only stop here briefly, passing through on their way to somewhere else. One of the few things Zhengzhou really has to offer — at least for wanderers — are its shopping malls.

When I was little, my family lived near Renmin Road. On weekends, our most common routine was to stroll through nearby malls and parks. Tall plane trees lined both sides of the road, and back then, Zhengzhou was still known as the “Green City.” (Later, due to urban planning and road expansions, much of the city’s greenery was lost during my growing-up years.) Even in summer, walking along the street it felt shaded and cool. The stretch of Renmin Road all the way to the Erqi Tower was, perhaps, the earliest version of a commercial zone in my memory. From Dennis Mall on Renmin Road to Dashanghai Shopping Mall then to Guangcai Market, you could always find what you needed along that path. In my mind, and Dashanghai Mall was the best shopping center in the Erqi district at the time. Its design, for the early 2000s, was unlike any other department store.

In 2015, a new mall called David‘s Plaza opened. It branded itself with the kind of positioning seen in first-tier shopping mall outside of Zhengzhou — targeting mid- to high-end consumers, offering luxury brands, an ice rink, and a more upscale cinema. Those years were marked by a kind of national euphoria: the stock market was booming, internet companies were fueling a wave of consumer upgrades, and on the surface, everything seemed to be thriving. But gradually, under the weight of all these shifts, the area around Dashanghai Shopping Mall began to decline, transforming into a cluster of counterfeit goods and low-end merchandise.

But it was around that time I started noticing something else: one by one, the once-bustling restaurants along the pedestrian street were closing down. And for Dashanghai Shopping Mall itself, the countdown to its closure had already begun. In the following two years, Zhengzhou was hit by catastrophic floods, followed by a banking crisis, unfinished real estate scandals and more. The city gradually spiraled into a strange cycle of decline. Its decay and abandonment seemed completely out of step with the times. You could say it failed to adapt, or that it simply settled into stagnation. You could also say it was devoured by fiercer competitors in the intensely saturated Erqi commercial district. But in the end, it was the pandemic and a mix of other forces that accelerated its downfall.

Around 2022, Dashanghai Shopping Mall officially went bankrupt and was put up for auction by the court. Its asking price — 200 million yuan — felt absurdly high for a collapsing economy, and unsurprisingly, no buyers came forward. As a result, to this day, it remains a mall with no management, no operation and no future. Now, its once-glitzy pedestrian street is covered with graffiti left by young people. In recent years, the rise of anime merch stores has brought a faint pulse of life back into the building, but it’s clearly not enough — it’s just a drop in the bucket.

Endure — again? Escape — again? Wait — again? How much more?

Why do I have to be liked by everyone?

Education has always been a tool of class solidification, keeping the poor outside the gates.

A life without thought is exile.

We will get married. We will raise a little cat together.

If I could start over.

Fuck your so-called stability. I want freedom.

I don’t believe in love.

Right now, I’m severely lacking a sense of security.

My curled-up, defensive state needs time to unwind.

If what they call “love” truly exists, I’ll embrace it — both its good and bad sides.

The rise and fall of Dashanghai Shopping Mall reflects exactly how I feel about this city: it tries to keep up appearances, but often fails to find cultural or spiritual coherence beneath the surface. As I walk through the streets, I try to imagine the feelings of those passing by, the stories each one might carry. I walk past the bankrupt mall, through the rotating plaza at Erqi, surrounded by cosplayers in elaborate costumes, by young people smoking against the stair railings of the overpass. And as I watch them slowly make their way toward the subway, I wonder — what is it that truly matters to them? And where, exactly, are they heading?