Across distance, silk forms a personal tactile bridge between Belgium and Hong Kong. Having been born and raised in Flanders and separated from my Chinese relatives, this fabric provided a means for me to savor family ties. I awakened each morning, as my kin did, in a bed covered by Double Horse silk quilts; enveloped by their soft warmth. Growing up interracial in a different culture, a different climate, the presence of shared objects created a sense of communality. Part of our day-to-day life, they are easily overlooked, but become part of a collective experience. The oolong tea boxes, the rice cooker in the kitchen, ginseng in whiskey bottles — elements not part of the typical Western household were staples in my childhood home, which housed a mixture of cultural elements. This sort of cultural melange comprises the DNA of each diasporic abode, and becomes a part of a cultural geography and identity — a visual landscape of belonging and being.

At the breakfast table, my mother would sit and drink coffee, dressed in her silk morning robe with Chinese embroidery on the back, each thread carefully catching the light. The material refracted photons from every angle due to its prismatic structure, creating a shimmering appearance. The way the fabric flows and drapes has been a perennial source of fascination for me. Part of playtime consisted of fashioning dolls’ dresses with silk fabric swatches, coming to understand the material’s versatility. When it came to selecting presents for visits to my kindergarten friends, my go-to choice would be the Chinese mementos stored in the closet. I would open the doors — the scent of mothballs unfurling — and uncover the selection of white silk hand-painted scarves. The detailed craftsmanship in each piece filled me with happiness and a sense of wonder. Being able to share part of my heritage through a gift was joyous.

Cold autumnal winds in western Europe would be buffered by navy Double Horse silk wadded jackets. I still have the jackets on hangers on display, some with patches of faded colors due to exposure to direct sunlight — the discoloration forming a symbolic marker of time. Over the years, fashion has been an instinctive way to express myself, to project how I want to feel — a visual and tactile mode of non-verbal communication that connects a family separated by language.

Looking Chinese without being able to speak it is a not uncommon experience among members of the Chinese diaspora in Western countries. Since infancy, I would hear the short daily calls from my father to his relatives — the melodic flow of Cantonese in the background — without understanding the content of the stream of words. As a child I noticed how, after the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People’s Republic of China, my relatives’ habit of speaking English slowly dissipated. Our conversations became less fluent, the search for words more conspicuous, rendering a growing sense of distance in communication during these long-distance calls. The inability to communicate through language with my relatives abroad was and continues to be a source of pain. Anti-Chinese sentiment where I grew up extended to how the Cantonese language was welcomed. This would manifest in the form of negative comments about China, sly remarks about Asiatic features and condescending jokes about phonology.

A common comeback in Dutch is “Dat is Chinees voor mij,” literally meaning “That is Chinese to me;” the English equivalent to the saying “Double Dutch.” The double irony of these idioms is not lost on me. Speaking Cantonese or Mandarin in a Dutch-speaking region would have added to being seen as an Other. Sadly, this remains the case today, with Sinophobia on the rise. Unfavorable views of China have exploded in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. I remember how on the tram or train during the start of the pandemic, fellow people of Asian descent would receive suspicious and unwelcoming stares.

Due to the pandemic it has been impossible to visit my family overseas. This separation highlights the space between us. Distance prevents the sharing of interpersonal space, of touch. The many missed family memories and lost days of communality, which inevitably occur when living on different continents, accumulate over the years. The silent side-by-side imperceptible shifts in habits, the mundane little joys all move along the axis of time, mounting to seismic proportions to be unveiled at each reunion. What is lost lies in the absence of expressions, behavioural cues and shared space. Proxemic and haptic behaviour form vital components in non-verbal communication. Their absence leaves a void in the visual and tactile culture of daily social experiences and interactions. Trying to find alternatives to replace conventional interpersonal communication has led me to contemplate the role silk has played in bridging gaps created by distance, cultural and language barriers. The haptic immediacy of the soft fabric lends an actuality to being “in touch.”

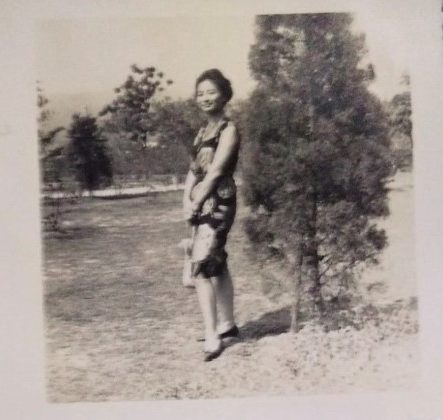

On my first trip to visit my relatives in Hong Kong and China, I was presented by my grandmother with her senior high school picture, normally kept tucked away safely in her wallet. Even though we could not communicate well with words, we found ways to engage in a visual dialogue. This being one of them. An undeniable expression of pride beamed across her face. My grandmother, captured on celluloid as a young woman in her qipao, emanated a timeless elegance. Her act of sharing a memory of keystone moments in her life arched the distance which prevented us from experiencing many of those moments in real time. Fast forward five years, my father surprised me with my own qipao by taking me on a visit to a tailor in the Panyu district of Guangzhou. Feeling like a kid in a sartorial candy store, being spoiled for choice. I finally settled on a silk fabric laced with sprigs of plum blossom embroidery. Traditionally the ume blossom represents perseverance and hope, often seen as the harbingers of spring. The whole process — from sketching a design to selecting together with the tailor the exact piping and pankous — is a memory I will always cherish. Being able to share it with my father, the talented tailors, and the lovely patron who was in for an alteration, enriches the garment with a personal history of interpersonal interactions.

My last trips to Hong Kong were hallmarked by hospital visits to see my grandmother, after her health suddenly deteriorated. In the care home, at the hospital, or during family dinners at my grandmother’s flat, the old photo albums offered a welcome distraction from her pain. Their nostalgia provided a small comfort. My grandmother’s face would light up when showing her family snapshots — a means of connection and escapism, especially during a time when her mobility was compromised. Seeing these snapshots for the first time, it was as if I was uncovering little puzzle pieces of my genealogy, witnessing the special occasions, travel outings, and get-togethers throughout the years. They offered insight into the individual stylistic flairs of my relatives and showcased how their fashion sense evolved throughout the years. Decades later, their outfits still look evergreen. Some of my favorite looks include my grandfather’s high-waisted slacks, combined with a white vest and a loosely tucked in silk shirt or my grandmother’s patterned qipao collection.

During the empty afternoons between the noon and evening visiting hours of the Tung Wah hospital, my aunt and I would stroll the meandering streets of Sheung Wah, taking our lunch breaks amidst the foliage of Hollywood Road park, scouring the stores for different teas to take back home together. She would tell stories of how my father at my age would often peruse the antique shops in the neighborhood. Walking along Po Hing Fong, beside Blake Garden with its ancient Chinese Banyan trees, we would wander along the bohemian cafes and art galleries. A favorite haunt was a silk shop with contemporary printed sheer designs.

Silk has become a personal bridge, its multisensory characteristics building connections within the cultural dualism which is part of my identity. Its visual and haptic qualities provide me with a feeling of well-being. Its threads weave a sense of belonging, providing a matrix for identity-building within a time and place in which the Othering of minorities is a daily reality. In its portable comfort the fabric offers a soothing salve against this, while symbolising the connection with my family members.

Emerald Liu is a Sino-Belgian writer and artist who has previously written for The Millions, Drawing Matter, and Greyscape.

Her work has appeared in group exhibitions in Antwerp and NYC. She draws inspiration from different cultural elements to form an open dialogue within each piece.