In 1998, not 20 years after the introduction of the television to the urban Chinese household, the first season of Huan Zhu Ge Ge aired for the first time. A Chinese-Taiwanese collaboration, it was an adaptation of the first novel of late Taiwanese writer Chiung Yao’s trilogy of the same name, a period drama set in Emperor Qianlong’s reign during the Qing dynasty. Over the next two decades, the three seasons would run and rerun, breaking Chinese television ground as one of the most widely-watched shows ever and cementing it as the defining series for an entire generation of Chinese people born in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

I first encountered Huan Zhu during the years I spent under the care of my paternal grandparents in Harbin, a provincial city in the far Northeast province of Heilongjiang, a few hours away from the Russian border. In that era, Huan Zhu Ge Ge replayed almost every summer and winter break during prime hours, and I would drop anything to watch it. It was that ubiquitous, that enthralling. As the century turned, in 2003, Huan Zhu followed me from Harbin to Beijing, where my parents finally made their home after shuttling between states in America. For years I would watch and rewatch it, following the storyline into the lauded second season, released in 1999 — which would come to be my favorite — and finally into the unpopular third and last season of 2003, anathematized for a change of key actors.

As I grew older, Huan Zhu faded into the rubble of forgotten childhood delights, alongside hawthorn candy, thick skin and wonder. I didn’t think of it for almost a decade. Then, after I left to the U.S. for college, I found myself inadvertently revisiting the series, always when I was back home in China. It wasn’t just one or two episodes; I basked in dozens at a time until entire seasons were behind me, watching the associations and sensations of my childhood reel out before me in the faces, music, and drama that were as youthful as I remembered, that had not folded at the feet of time.

What was I looking for? What new excitement could be elicited out of a series as old as myself?

Initially, I naively thought that all the hours I lost in the Huan Zhu hole were driven purely by nostalgia and indulgence in the finely-tuned catharsis of drama. As I continued revisiting it at pivotal moments over the years, I realized that superimposing a moving image of nostalgia over my present life allowed me to see the refracted changes and desires that were otherwise elusive to my eye. Through the double exposure of past overlaid with present, of home and abroad, I saw loss and change, growth and gain, and an increasingly blurry locus of home. But most of all, my nostalgia aided the communication between my past and present selves and helped me see just how close the anchors that define an era, personal and sociopolitical, are to being lost.

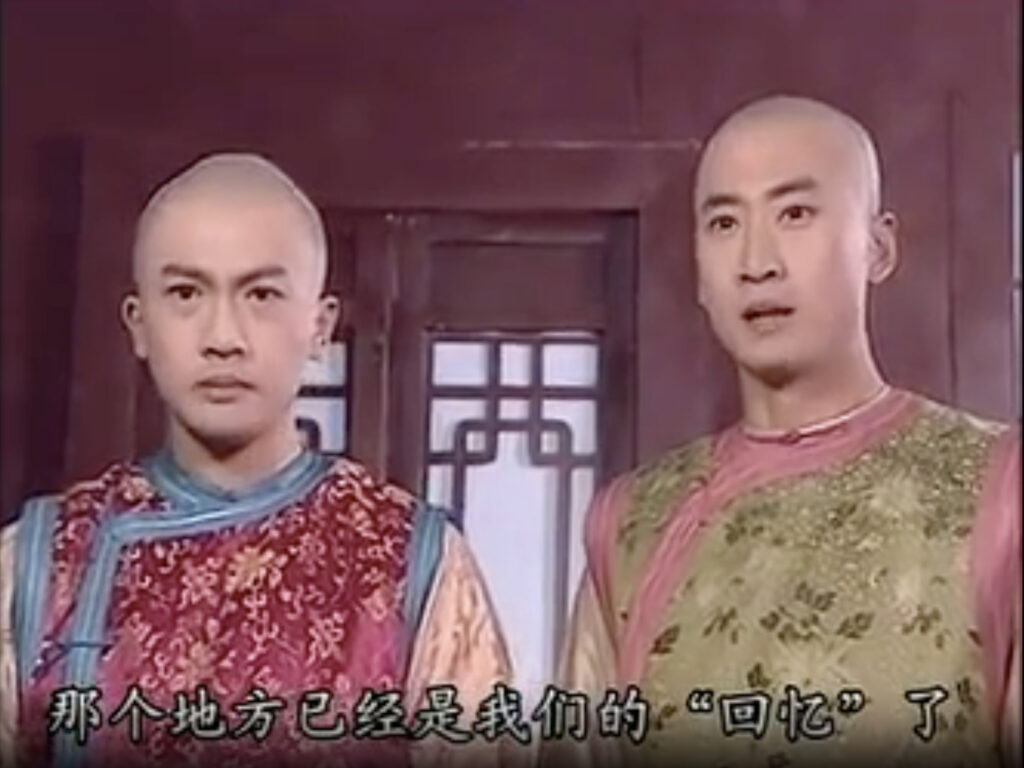

Caption reads: “That place has already become a “memory” for us.”

“Nostalgia sanitizes and blurs; it’s the large distances of time and space which nostalgia traverses that gives it a utopian filter. The past possesses no inherent quality that renders it paradisal but rather becomes paradise precisely because it is lost.”

While nostalgia is now understood to be the wistful emotions brought about by an encounter with memories of the past, the term’s origin was much less whimsical. A compound word consisting of the Greek words nostos (return, or homecoming) and algos (longing, or pain), nostalgia is literally the suffering due to yearning for the homeland. It was coined in the 17th century when Swiss physician Johannes Hofer employed it to describe the homesickness observed among Swiss mercenaries throughout European monarchs. We now associate it with poetic sentimentalism, but nostalgia was first seen as a medical disease, with symptoms including “weeping, irregular heartbeat, and anorexia.” This view of nostalgia as medical disease persisted throughout the 19th century until, at the start of the 20th century, it was reclassified as a psychiatric disorder. Developments in psychoanalytic and psychodynamic studies then transformed the understanding of nostalgia into a “subconscious desire to return to an earlier life stage.” Over the next century, the medical severity of nostalgia continued to be downgraded to a variant of depression still associated with homesickness, loss and grief; until at the turn of the millennium, nostalgia and homesickness finally diverged into separate and distinct sentiments.

Unlike the home of homesickness, the home of nostalgia — the home of the self — is frozen in time and space. Kant claimed that for the Swiss and the rest of those suffering from nostalgia, “it is not the place of their youth that they seek but their youth itself.” In The Future of Nostalgia, the late cultural theorist Svetlana Boym defines nostalgia as a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed, deftly delineating it from homesickness, which conceives of “home” as still accessible. Be it youth or place, the longing of nostalgia points distinctly to an object that is unrecoverable. In Proust’s words, the true paradises are the paradise we have lost. Nostalgia sanitizes and blurs; it’s the large distances of time and space which nostalgia traverses that gives it a utopian filter. The past possesses no inherent quality that renders it paradisal but rather becomes paradise precisely because it is lost.

Rewatching Huan Zhu Ge Ge did not make me want to believe that home was ever paradise; it simply charted the growing distance at which I was adrift from its island. But it wasn’t just my own youth and its unrealized dreams that became irretrievable; it was also an entire generation’s vision of China and of being Chinese — its hopes and possibilities — that became obsolete, that had slipped away from us before we could understand, lost to the river of time.

“When I return to Huan Zhu Ge Ge again as an adult, my former self and the China of its era would seem like a lost paradise.”

— 还珠代 —

Translated as “My Fair Princess” or “Princess Returning Pearl,” Huan Zhu Ge Ge follows a boisterous civilian orphan, Xiaoyanzi, after she befriends the illegitimate daughter of the emperor, Xia Ziwei, who has traveled from Jinan to Beijing after her mother’s death to attempt make contact with her father. The series covers their trials and tribulations as they make their way into the Forbidden City and, after an identity mix-up, are both made “ge ge” — a title for imperially-born unwed girls.

Xiaoyanzi is the imperial palace’s worst nightmare. Boyish, uneducated and with a love for martial arts sparring, she is an exercise in imagination of how an oppressively regimented epoch attempts to contain the free spirit. Vicky Zhao’s Xiaoyanzi steals the spotlight over 72 episodes thanks to her convincing innocuous irreverence, befuddlement at the rules and rhythms of the Qing dynastic court, and Zhao’s large and expressive double-lidded eyes.

Her too-perfect character foil Xia Ziwei is a study in feminine discipline and tactful deference. She excels in all four of the classical Chinese arts; she is the Ideal Woman. She is also a textbook damsel in distress: frequently ill, always struck by misfortune, and physically defenseless. Attentive, a mediator, and always ready to sacrifice herself, Ziwei is resigned where Xiaoyanzi is vengeful; apologetic where Xiaoyanzi is enraged. Ruby Lin’s Ziwei speaks carefully but emphatically, and her wide-eyed face of worry signals to the audience that while Xiaoyanzi is enjoying herself, oblivious, something may be amiss.

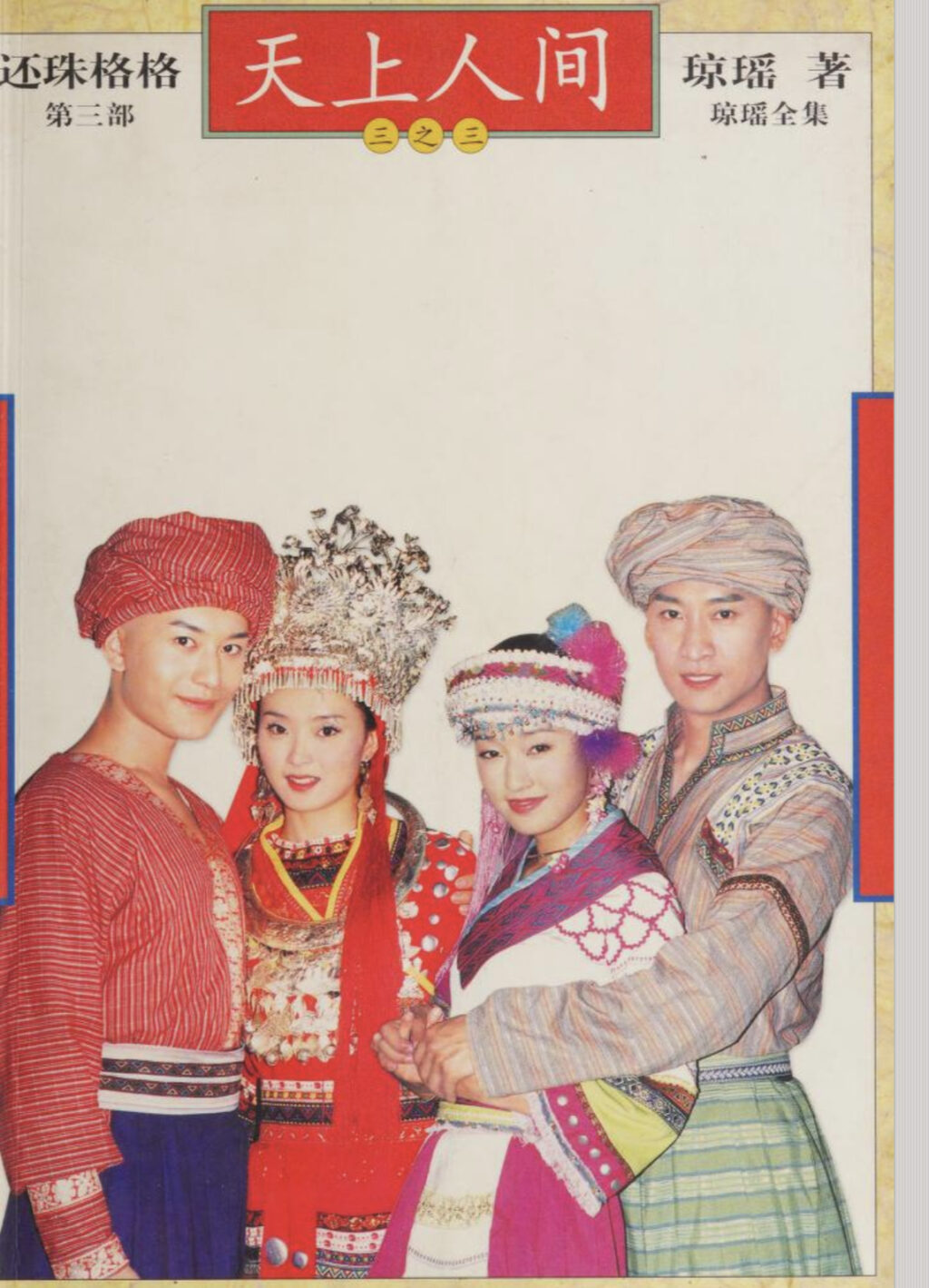

Through two seasons and a third in which Lin and Zhao are swapped out (to viewers’ dismay), the two charm and infuriate, they fall in love (they have to) with the emperor’s son and right-hand man, forming an inseparable quartet. Enemies lurk constantly in the shadows, plotting to expel or behead the two commoners. A story that opens with the search for bloodline becomes just as much about chosen family, and eventually about exile and the longing for an imaginary home that is capacious enough to accept them.

Huan Zhu Ge Ge combines period drama with martial arts film with ‘90s chick flick with family-friendly comedy. Perhaps this is why it appealed to the retired and the uninitiated alike: those willing to believe in the series’ moral idealism. Huan Zhu’s characters prevail because they act in the interest of justice for the common person, going so far as to commit treason. This all-encompassing humanity, in turn, wins the hearts of everyone they meet, especially the emperor, and definitely the audience.

Over the two decades after its initial release, Huan Zhu Ge Ge would be re-broadcasted 16 times, cementing its place as one of the most iconic television series in contemporary China. It’s among the top three most-viewed television series in China, surpassed only by the epic 1982 adaptation of Journey to the West, and the 1987 adaptation of Dream of the Red Chamber. Season 1 of Huan Zhu reached a national viewership rating of 62.8%, and season 2 a rating of a whopping 65.95%. It had viewership in Vietnam, South Korea, Mongolia and across the Mandarin-speaking diaspora. The show catapulted its mostly little-known cast members into fame overnight. In 2011, it was remade in China with a new cast. There are entire Tumblr communities dedicated to the series, GIFs of characters sending meaningful looks or shedding tears replaying on loop into eternity.

Part of the series’ appeal to children and those living in the diaspora is that Xiaoyanzi is not only an entertainer but an educator. Her level of literacy is roughly that of a third grader’s, which forces characters around her to go to lengths to explain Chinese proverbs, idioms and characters. She then knits her brows and moans with frustration, and her befuddlement is a significant source of the show’s humor. Xiaoyanzi as colloquial dictionary, as linguistic guide, must also play a factor in the show’s reach and popularity abroad.

Throughout my own childhood in China, Huan Zhu Ge Ge was omnipresent. The characters’ faces were on my pencil cases, erasers, notebooks. My grandparents bought me Huan Zhu tracing pads, and I spent slow simmering afternoons of summers gliding my pencils along the faint lines peeking through the tracing paper until my wonky shapes coalesced into their complete forms. At one point I dreamed of a life lived under a different name — Xia Ziwei’s name — before understanding that I loved the name only because I loved the character. The name was hers and hers only, was cemented in my mind by this paragon of feminine learnedness, by Ruby Lin’s soft, elegiac features.

Then puberty came: an encoded exile, a biological divider between the before and after. My friends and I cold-shouldered not just the honeyed season of childhood but also the dog-worn homeliness of everything that had no social capital. Even in the unique ecosystem of anglophone ethnic Chinese living in China, American was the Major culture, and Chinese the Minor. We coveted authentic Abercrombie & Fitch, a taste of avocados mashed the Chipotle way, teenage desire à la Katy Perry. I shunned red socks at Lunar New Years, scorned the saccharine aesthetic of kawaii.

Events during my teenagehood also set into motion a fracturing of my mind that would definitively separate the self I knew and the one that would come out of it 10 years later. When I return to Huan Zhu Ge Ge again as an adult, my former self and the China of its era would seem like a lost paradise.

“Watching Huan Zhu from the future reads as a manifestation of both national nostalgia and an avenue into a nostalgia for a home that, to the diaspora, never existed.“

— 落叶归根 —

Though the setting is historical, Huan Zhu Ge Ge is not a historical piece. While it wears the aesthetics of the Manchu dynasty, these historical fixtures are neither particularly accurate nor significant to the story, and it is clear that the series is not particularly concerned about either. Male love interests in the series bemoan polygamy, wax poetic about the merits of marriage born of love. Xiaoyanzi despises social hierarchy (she forbids kneeling and kowtowing in her imperial residence). These four core characters, with their modern sensibilities, are there as vessels not to critique the Manchu customs of the 1700s but to instill more liberal ideas in the audience of the late 20th century.

Watching it now, the show feels ahead of its time. Despite being the last dynasty, the Qing Dynasty was conservative and insular. In Huan Zhu, an entire family is killed for one man’s cached anti-Qing beliefs in a poem. Ziwei’s love interest, Fu Erkang, explains the regular occurrence of the literary inquisition, and expresses his dreams of a future for the Chinese people with freedom of speech and of thought. When the emperor recommends that Erkang take another woman as wife alongside Ziwei, he is aghast, and once again, outlines his hopes for a future in which love does not need to be split or shared.

No wonder, then, that Huan Zhu Ge Ge has found popularity in the American diaspora. Friends of mine raised in America recall Huan Zhu as a transportive anchor to an unreachable homeland, a cultural tether. The series provided Chinese-American children a glimpse into a glorious homeland, even if inaccurately portrayed, and allowed them to immerse themselves in a world of Chinese characters who could fall in love and mess up and triumph, who were allowed the fullness of human experience, who were rulers and servants and thugs and warriors, and whose burden of explanation was limited only to how 一丘之貉 shouldn’t be read as 一兵之貓, that Xiaoyanzi’s ability to turn 君子一言 驷马难追 into 君子一言 八马难追 is simultaneously outrageous, hilarious and ingenious.

Over the past three decades, China in the Western eye has transformed from a pitiful T-shirt label to a global bully threatening the Ameri-centric world order. Amidst the shifting portrayal of ethnic home from one antagonist to another, Huan Zhu offered overseas children and adults an imagination and a memory of a homeland that was free of the burdens of representation, that was proud and resplendent in its heritage, and that was progressive and glorious. Watching Huan Zhu from the future reads as a manifestation of both national nostalgia and an avenue into a nostalgia for a home that, to the diaspora, never existed.

“But at the end of the day, when the rebellion is done, when the myth is savored, nostalgia becomes a forced reckoning of the passage of time, of all the years away from home. “

— 回忆城之泪 —

While I rewatch parts of Huan Zhu Ge Ge as an adult in 2016, it is in 2023 when, parallel to a physical homecoming, the nostalgia of revisiting Huan Zhu truly –– to reference a paper by Constantine Sekkides in Current Directions in Psychological Science –– facilitates continuity between my past and present selves.

For the first time, my time away from home was imposed and not voluntary. The COVID-19 pandemic has kept the Chinese border closed since 2020. I am away for four years, during which I don’t see most of my family, and in that period of time of anxious waiting and isolation, being Chinese in America — and also being Chinese in China — slowly took on a more fraught context. In Brooklyn, I am physically assaulted twice in the street, and in China, Shanghai starves under COVID-zero policy and 10 Urumqi residents are burned alive in a building.

What happened to Erkang’s vision of a China freer than his own? The freedom that Xiaoyanzi and the quartet desire may have been alive in Chiung Yao’s 1999, but has certainly been crushed by now. Knowing what comes after, it’s hard to think of the China into which Huan Zhu was born as anything but hopeful.

When I finally step off the plane at Beijing Capital International Airport in May of 2023, I am steeped in a feeling of uncanniness. The airport appears as I left it. The rest of life in the city, too, has a breezy, amnesiac feel to it. Only in the shadowed empty lots in the backs of hospitals does any memory of the past few years remain. Barbara Cassin, in her book Nostalgia: When Are We Ever at Home? describes Odysseus upon his return home after twenty long years as being “there at last, but [also] not at all there […] Nothing is more terrifyingly strange, nothing more uncanny, than his homeland.” Appropriately, uncanny comes from the German term unheimlich, which translates into unhomely. The uncanny is the frightening unfamiliarity in facing what should feel like home.

Towards the end of my time at home, beckoned by the tide of newly accessed memories and sensations, I found myself typing 还珠格格 into Baidu’s search engine, possessed by an irrational fear that there would be no video results. Stranger things, certainly, have happened on the Chinese internet. But Huan Zhu endures. All three original seasons, as well as the new adaptation, were available to stream.

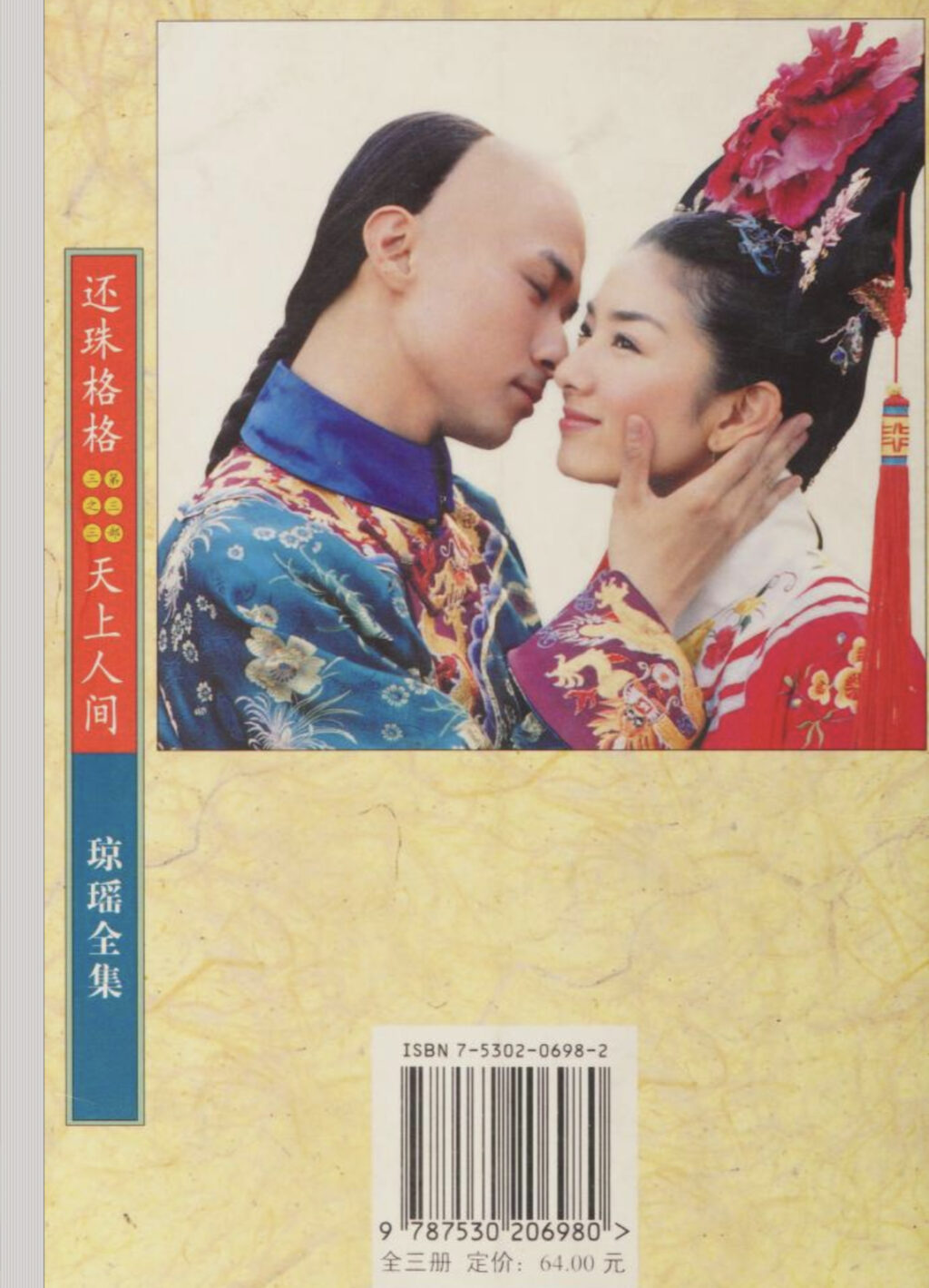

Caption reads: “You’re finally back.”

I watched the entire second season piecemeal over two months. The initial rush of familiarity bobbed its head like a new year. Many plot points and emotional beats gave a familiar nostalgic fizz as I watched: Xiaoyanzi and Yonqi chased by dogs after unintentionally stealing persimmons, Xiaoyanzi and Zi Wei pushing the empress into a basin of cold water while drunk. Yet in that comfort of recognition sheltered an uncanny realization that while the object of nostalgia has remained static, the nostalgic subject has changed.

The crux of the second season is that Xiaoyanzi and the quartet steal away the emperor’s favorite forlorn concubine from Xinjiang for her to reunite with her beloved. Their cover-up story eventually unravels, and in a burst of rage the emperor sentences them to death, but with their friends’ aid, the group successfully flees the palace.

In the newly settled silence of the palace absent of its biggest troublemaker, the emperor (Zhang Tielin, China’s choice actor for portraying Qianlong) paces the halls. We see him vacillating between fury and regret, humiliation and fear. He pays visits to the princesses’ residence, his gaze far-off and unfocused, and he muses on how, without people to share it with, life is like a dry well.

In 2016, I had discovered newfound sympathy with the abhorred empress, but I now found myself moved by the emperor, a character I had never given second thought to as a child. I had been that rebellious, tempestuous teen. I, too, had disappeared. I had made it hard to be my father.

At the end of the second season, Emperor Qianlong travels from the Forbidden Palace to Nanyang, roughly six hundred miles by horse-drawn cart, with the hopes of convincing his children to come home.

Zhang Tielin gives a momentous performance in a monologue in which he laments the misunderstandings and his own pain of forcing his children to desert him. He abandons the first-person pronoun reserved for emperors, zhen, for the standard humble pronoun wo, his eyes moist and his voice breaking as he speaks. “In this moment, I’m no longer an emperor. I’m only a father who has lost his children — a father without pride and without rage.” The emperor’s anger is frothed as a ruler, but his heartbreak is felt as a father. I find myself holding back tears.

At the end of The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym concludes that ultimately, we are nostalgic for a time when we were not nostalgic. For a state of mind not yet initiated into loss.

In that decade separating childhood from adulthood, that decade away from Huan Zhu Ge Ge that I passed in and out of psychiatric hospitals, the crux of so much of my pain was the belief that nothing changes, that I had no potential for change, and therefore that the pain would last forever. And so I lost time. I lost years, I lost friends, I lost lovers and opportunities and the tableau of selves we think we get to construe into our futures when we are young. But while I, unaware, was slowly changing, things around me changed faster, and without me. When I finally emerged from that decade-long deep fog, there were a myriad of things that beckoned irreversible loss. There was pandemia and there was war and there was cancer and addiction and throughout it all, there was the ticking hand of the hours, facing me at the end of the road.

In an article published in Analysis, Scott Alexander Howard posits that there is an incorrectly assumed requisite of nostalgia: that the past is preferable to the present. Never in my moments of rewatching Huan Zhu Ge Ge did I think that the soft labyrinth of childhood was preferable to the lonely, doubt-filled skies of adulthood. Nostalgia, Boym states, is rebellion against the modern idea of time. My continuous revisiting of Huan Zhu Ge Ge was my desire to “turn [history] into private mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.” But at the end of the day, when the rebellion is done, when the myth is savored, nostalgia becomes a forced reckoning of the passage of time, of all the years away from home. When I finally came home, I stood in my childhood bedroom and looked around me. I almost lost all of this, I realized, taking stock of the breadcrumbs of years, the evidence of a more precarious self retrieved through the telescope of nostalgia. I had almost reached the point of no return.

Nostalgia illuminated my capacity for change: all of this can be and has been overcome. It also shined a light down the other end of the tunnel. All of this, gestured nostalgia, can and will be lost.

In the early stages of their exile, Xiaoyanzi and the quartet decide to travel towards Yunnan, a mountainous province in the south of China bordering Myanmar, famed for being a land of eternal spring. They imagine it to be a place of ideals, a place without persecution and without war, a place that they could call home. They also debate over what monikers they should use to avoid saying “emperor,” “forbidden city,” and any other term that might give away their identities. The Forbidden City becomes “Memory City” because it contains their most cherished memories, whose subjects also eventually expelled them.

Yet despite their dreams of a life of eternal spring, at the end of the season, deep in autumn, they return to the palace with the emperor. While they were moved by their imagination of a true homeland, it is their father’s love — this father who represents an entire nation — who heals their hurt, who brings them home.

To return to Boym’s text: “nostalgia is the longing for continuity in a fragmented world.” It is, too, a longing for unity within a fragmented self.

Huan Zhu Ge Ge is my Memory City. As the years pass and home in every sense becomes harder to access and the cultural halves of myself harder to unite, the nostalgia of Huan Zhu Ge Ge will remain that place of eternal spring, my home away from home. It will always point to the paradise that is made by the possibility of being lost.