Hmm, are people really willing to let go of power?

Chiraag Bhakta has been working under the pseudonym *Pardon My Hindi since 2002. His practice is rooted in collecting objects from various times and environments building upon a theme, which primarily relate to identity, history and popular culture. His work draws from his background in the design industry and varies in medium including Printmaking, Collage, Photography, and Assemblage. He was raised in an independent motel on a NJ freeway with rotating extended family. [From his website.]

A section of Bhakta’s exhibit, “#WhitePeopleDoingYoga” featuring a shrine to white yogis dressed as Indian gurus. The Asian Art Museum in San Francisco objected to the shrine, calling it “offensive to Indian people” and it was removed from the show. The banned work was featured in his 2019 show “Why You So Negative?” at Human Resources in LA (Photo by Maria Kanevskaya)

In 2019, Chiraag Bhakta penned an article for Mother Jones about his experience working on his 2014 installation, “#WhitePeopleDoingYoga,” with The Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. In the article, he reveals the condescension he faced from a mostly white group of curators for daring to put together a show that commented on the commodification and appropriation of yoga. We spoke with Bhakta, an outspoken antiracist, about racism in the American art world, and the personal experiences that shaped his work.

Edited excerpts from the conversation follow.

Chiraag Bhakta I grew up in New Jersey and my parents grew up in Gujarati farming villages in India. In the late ‘60s they got arranged, and a couple weeks later my dad came over to the States because he was accepted to a college in Philly to get a master’s degree in chemistry. After the British left India in ‘47, the Russians were poaching talent and so the U.S. followed with a test program of 100 visas per year. They stopped that and said only people looking to get their master’s or doctorates can come here. My dad was a part of that wave. So the way that the U.S. government designed the Indian-American community is very specific, just like they do with every community they invite. They built a community of people with master’s and Ph.D.s, and used the community as a tool — I think Reagan was the first to popularize the term “model minority” — and said, “hey, look at the Indian American community! Why can’t you other communities do that?” Go fuck yourself, you design each community in different ways. Don’t use us as an example to put down another community while you benefit from it. It gets really troubling when all of a sudden the community itself acts like a puppet and starts saying the same thing.

Ariana King So in your community you met a lot of people who bought into the “model minority” myth?

Chiraag Yeah, a big part of it. It’s being talked about now, but I think it’s deep-rooted, especially with the colonial past. There’s a lot of layers to unlearn and we’re having to look at the structure in a different way from what was instilled in us.

Eventually my parents saved enough money and got the community’s help to lease and eventually buy a motel in New Jersey which we also called home. This became a hub for the extended family to come into America. There’s this whole community of Gujarati Americans that live and work in motels. I’ve been working on an ongoing project since 2005 photo documenting and collecting around the community. Ten photos from that were part of an exhibition at the Smithsonian in D.C. in 2014. It was really my first big look into these big [art] institutions. That was the same year I showed “#WhitePeopleDoingYoga.” I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a part of it. But I remember them saying “if it’s not part of the Smithsonian, it’s not part of American history.” It’s like, fuck. In a way they’re right, and it’s kind of gross — we see who controls the narrative and we’re seeing it being fought. Obviously I ended up deciding to contribute to the exhibition. But going through those experiences and seeing how the Asian Art Museum wanted to mold my voice into a voice they felt comfortable with…

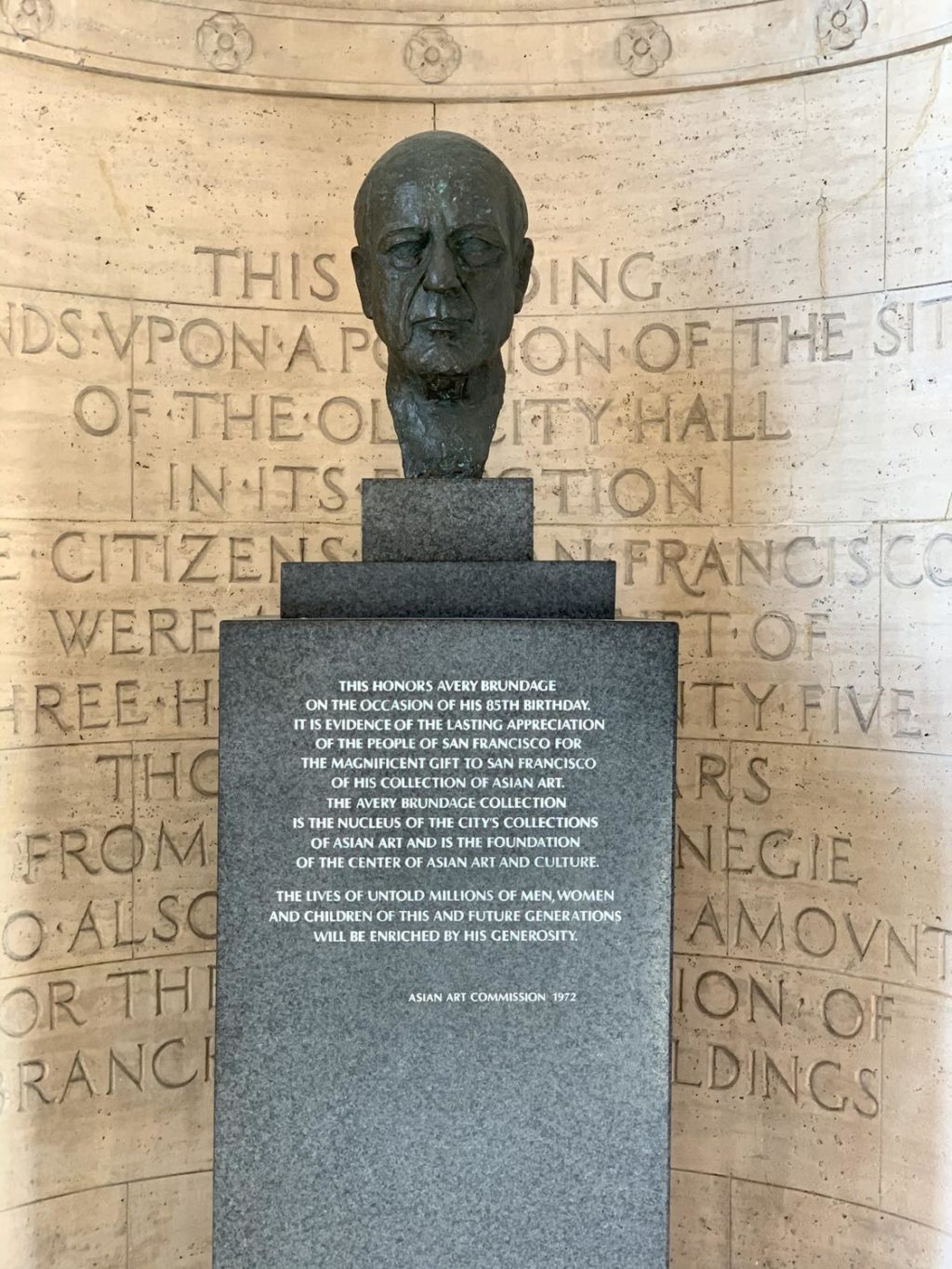

The bust of Avery Brundage in front of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco before it was removed (Photo by Chiraag Bhakta)

Ariana Do you think within the past six years anything has changed?

Chiraag I’m sure things have changed and they’re going in the right direction, but man, it’s taken you this long to remove the bust of a Nazi sympathizer? And they’re just going to put it in the basement of the museum, and it goes into another person’s collection. The objects in the museum were stolen. [Brundage] was a looter. We’ve seen it with the British museum — “well, if we have to give up one piece, we have to give up everything.” It’s like that one string of the sweater that unravels everything. So I feel like there has been change, but they’re making cosmetic changes rather than real structural changes that need to be made. For one thing, the breakdown of the Asian Art Museum’s staff is 50% white. Some of lead curaters are white. I’m not saying white people can’t work there, but if these leaders were really on the same page and want to be allies, they would be stepping down and trying to put a person of color or of Asian representation to lead these departments. Hmm, are people really willing to let go of power? Probably not. But that being said, I don’t think diversity alone is going to solve it. It’s the whole structure of a museum like that and what it represents — Orientalism and all that shit. They’re trying to throw diversity on it. Diversity is great but it’s that structure that we need to focus on, and that can easily be distracted by diversity.

Ariana What could be a good first step then, beyond “throwing diversity” on the problem?

Chiraag I really think institutions like this need to be dismantled. This is stuff they don’t want to hear — they want to exist. It’s hard to talk about. The control needs to be decentralized from its donor and owner class, it needs to be grassroots.

Ariana Though I wonder — maybe I’m biased because I work within the structure — but what I see from a younger generation and what I’m hoping to be a part of is, just steal away with the skills and networks that we can get from these very well-funded institutions, and once we have that, put it somewhere else. What we’re trying to do with FAR—NEAR is give the mic back to Asian artists. We want to move away from those Orientalist perspectives and reshape the conversation.

Chiraag So you’re building a new structure.

Ariana Right. Because I know it’s hard: how do you build from nothing? You need to kind of use what’s already there. So I think your working with the Smithsonian gave you a platform, but once you have the resources, you can put them elsewhere. I think if we choose to spend our money on supporting “up-and-coming” artists, artists of color who aren’t able to move within the structure — we can use what we have to create our own structures.

Chiraag You’re right. Why ignore those resources? Pull from that shit. The progressive people within those institutions will be part of that dialogue and pull those resources outside of that structure. But we’re seeing people that — it doesn’t matter if they’re white or Asian — they’re part of that structure that is feeding white supremacy.

Ariana Right.

Chiraag So what I’m saying is, even if it’s a diverse board — and I’ve seen it, experienced it at other institutions — they elect the first non-white head curator at a major institution, but when you look at what they’re actually doing it’s just like, man, you’re just another mouthpiece. It’s really frustrating. They might get away with more because they don’t have a white face. I felt it was my responsibility as an Indian American to call out the largest institution of Asian arts in America. All of these institutions are using black lives as a marketing trend, but some aren’t getting called out because they’re “diverse.” That agenda is still there, and I feel like it’s our responsibility to call out these institutions, even the ones that don’t have a white facade, and to really check them.

Ariana King

Chiraag Bhakta