Preface: Mai Ling Speaks is a series of online performances, lectures and interviews connecting the active voices dealing with the anti-Asian ramifications of the current global pandemic. The program aims to diverge the discourse towards individuals and communities and, at the same time, create a discursive platform that bridges artistic practices and theories. More info on the previous episodes of Mai Ling Speaks here.

As part of the programming, Mai Ling tasked journalist Sandy Chung to conduct an in-depth discussion on family, identity and disrupting traditional space with photographer and artist Guanyu Xu. The following interview has been edited and condensed.

“Sea (Lake Michigan)” (2014). Courtesy of Guanyu Xu and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Guanyu Xu is a Beijing-born artist based in Chicago. Xu’s works are a visual commentary on subverting stereotypes of Asian identity and sexuality, as well as on breaking demarcations of geopolitical and domestic spaces. Works like “Temporarily Censored Home” transform the traditional space of his parents’ home into a ‘queer space of freedom and temporary protest.’

“Alpha Male” (2018). Courtesy of Guanyu Xu and Yancey Richardson Gallery.

Sandy Chung Can you describe what your work and motivation is? Works like “One Land To Another” and “Temporarily Censored Home” come to mind specifically.

Guanyu Xu I came to the States in 2014, arriving in Chicago during a bad winter. I was a transfer student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Before I had studied photography at Beijing Film Academy, where I had taken elective classes that dealt with industrial style filmmaking. That was where I gained knowledge of Hollywood films, but not critically. It talked about how to make a great commercial film instead of talking about the history of racism or how demonized people of color are in Hollywood films. At that moment, I was merely absorbing racist representations without knowing it was racism. When I got to SAIC, I took classes on race in cinema and Asian representation in film—I started to learn more critical theory towards media and culture.

So at that point I started the project “One Land To Another,” which became a slowly growing project. I started taking portraits dealing with fear and safety, as a person who just came out. I was also taking images of American landscapes to get to know the US a little better. Before, I was merely absorbing the landscapes, the ideology and the cultural values from Hollywood movies in China. Then I started to make portraitures with other gay men that I found on dating apps. I collaborated with them to show different relations and confront the lack of Asian representation. If you think of fine art photography, you don’t see many Asian bodies and if you think of mainstream cultural productions, you don’t see many Asian or Asian gay characters in film or TV shows.

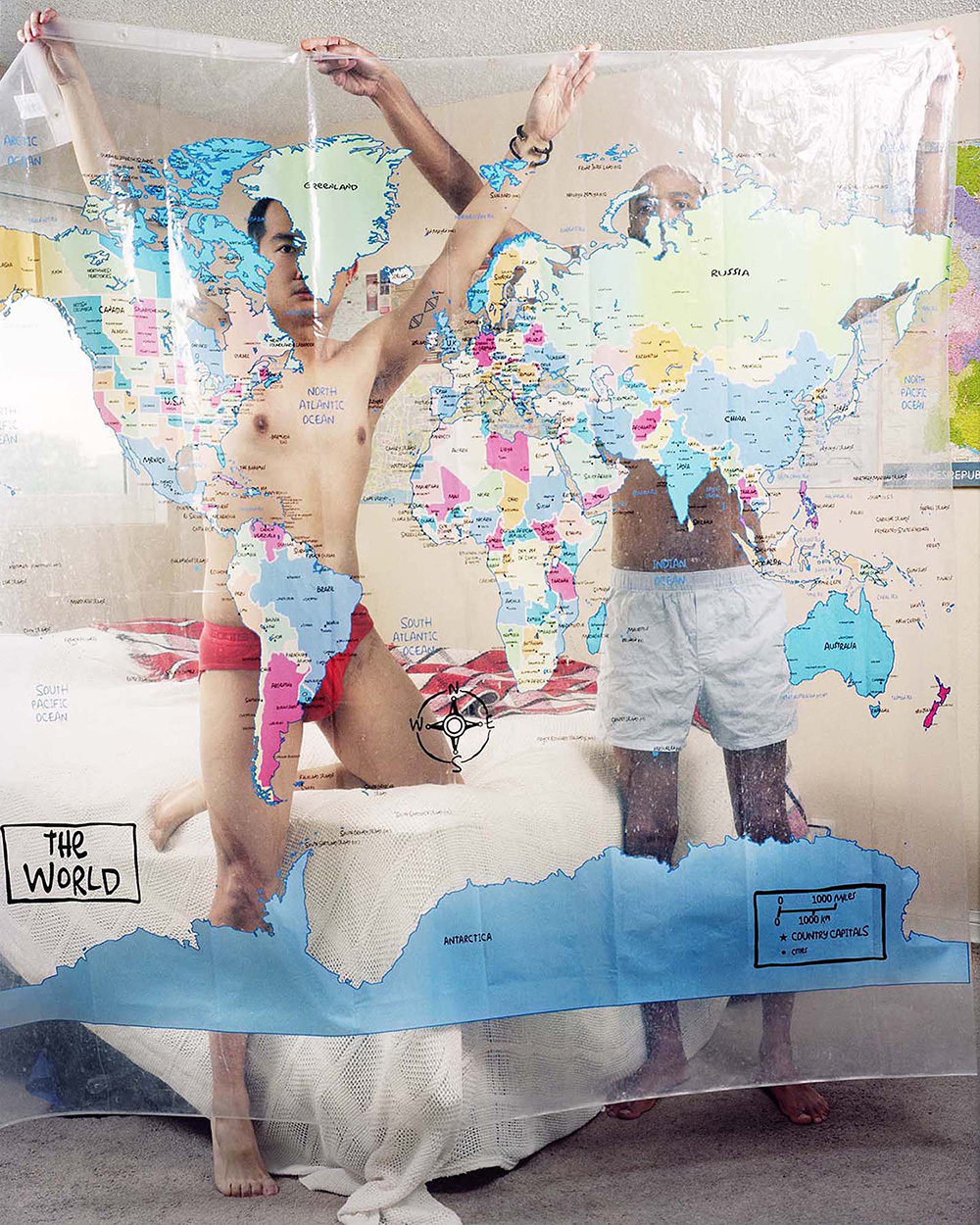

“One Land To Another” thinks about how to create cinematic stills to show different narratives through photography. And it also started to deal more and more with politics after Trump’s election. In grad school, I used the breaks to go to LA and Philly to take images for “One Land To Another”. I was thinking about different geographic locations, how I would encounter new personalities and create images that are more deliberately thinking about the backdrop of the election, of Trump, and use of themes on neo-nationalism or even white supremacy. That was in the back of my mind. Like you see images where I’m with another person holding a shower curtain of the map of the world, which belongs to the person. I was deliberately thinking of how to perform for the camera and perform for the viewer to send a message. So it’s alway kind of changing, the project is always mutating because the world and my worldview is changing.

“Map of the World” (2018). Courtesy of Guanyu Xu and Yancey Richardson Gallery

“The Dining Room” (2018). Courtesy of Guanyu Xu and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Guanyu Xu This project migrated back to my home in Beijing. I took two trips during grad school where I printed out images, folded them in a cardboard box and put them in my luggage to bring back to Beijing. While my parents were gone, I hung those images in the apartment and eventually documented the installation as photographs. The images in the installation are combinations of portraitures of both me with other gay men, but also torn pages from Hollywood film magazines and fashion magazines with male models that I collected growing up in Beijing. So thinking of the juxtaposition, I had the history of consuming these cultural products and then eventually I came to the US and I suddenly realized those images were not neutral. They embedded a certain desire; they created a hegemony where I would never really feel completely free.

Those images, they were created for only certain types of people, mainly for white middle class Americans that believe the US is the best country in the world; that only believe in heterosexual relations. They also grew up consuming films that created yellow peril, dragon lady and yellowface. We are still dealing with whitewashing in Hollywood. So thinking about how I juxtapose my response and my performative self-portraits with other men, those images formulate my desire and create a clash in this space, so I can eventually generate a new potential future for myself.

I think the work challenged the really conservative aspect of growing up in Beijing, specifically with my parents. But it is also a comparative examination between the US and China—in a way both societies limited my freedom differently.

“Parents’ Bedroom” (2018). Courtesy of Guanyu Xu and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Sandy How is it living in the US now with escalating xenophobia and growing anti-Chinese sentiments? A lot of this was embedded in your work before the coronavirus crisis, but how has it now impacted your work?

Guanyu In general, politicians and normal Americans never really reflected on the history of anti-Chinese sentiments or slavery. So racism didn’t really go away, it was just hidden. The type of scapegoating Trump used in 2016—you see him using a similar strategy of scapegoating now. Most of the time, I stay at home. In my neighborhood, there are a lot of Asians and Mexicans in the community; it’s pretty safe for me. I have a studio that’s an hour away by public transportation, but I’ve completely avoided going there because it’s not safe in terms of corona, but it’s also not safe for me to potentially encounter lots of people. So i think it’s just sad that xenophobia is happening because people are not really educating themselves, but the larger media and the education system in the US—they are now trying to educate people to better understand history and what’s going on.

“Worlds Within Worlds” (2019). Courtesy of Guanyu Xu and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Sandy Physical spaces seem to be a big part of your work. What is it like for you now in terms of limitations with space?

Guanyu I was actually working on a new project called “Resident Alien.” I was planning to photograph people I knew who needed to get a new visa because they were ending their student visa, or they were dealing with H-1B or O-1 visas. People that have stayed in the US for a pretty long time, but they are still trying to figure out their visas—people like me. And I was planning to take images in their home and then bring printed images to install in their places. This was thinking about how their house in the US is always in a really temporary state because at any moment their visa could be revoked; it was thinking about Trump’s recent suspension of immigration visas and green cards. Because of the virus, I cannot really go to my friends’ places to take new images, just thinking about the safety of everyone. I also don’t have access to printers. Everything is suspended. I’m trying to work virtually, I had this video work called “Complex Formation” where I used 3D animation and 3D generated images with dialogue between me and my mother. So right now I’m trying to work virtually to create collages.

Sandy Has being in a contained space given you a different inspiration?

Guanyu I don’t think coronavirus has given me any new inspiration. It’s just made me feel completely drained. It’s really difficult for me. I started worrying in early January because my parents were in Beijing and what was going on in China was horrific. Everyday I would wake up and check different news about the situation and in February I saw everything was going better in China because of the lockdown. And at the end of January, I was worrying about what was going to happen in Chicago. It seemed to be fine, but it was just the appearance of fine. At that time, Americans still didn’t believe in wearing masks, they didn’t believe the virus could be transmitted so easily and at such a high rate. You didn’t see much in terms of government action or media action to talk about it. So I also let my guard down and I was not really worried too much anymore. But then in March, everything started to become real. I went to NY for the Armory Show at the beginning of March and I had this constant debate of “Should I wear a mask in the subway?” or “Will I be targeted by people who think I have the virus?” I was so anxious when I was there.

Sandy Did you end up wearing a mask?

Guanyu I was in NY for 4-5 days; I was wearing a mask when I landed, in the airplane, and then I wore it in the subway to my hotel. After that, I think I only wore it once in 5 days. I was anxious because at that time, it was already on the news about people being targeted and attacked.

Sandy What’s the overall reaction you’ve gotten to your work since it is so much more out of the mainstream?

Guanyu I think most people are really fascinated by the fact that my parents still don’t know about the installation. They never thought I would ever really be that big and on the internet. If you use the Chinese version of Google to search my name, you will find my website. So if they look for it they will see it, but not so far.

Sandy What would be your ideal take away from someone looking at your work? Now that you are putting out a more inclusive view of what it is to be Asian.

Guanyu Probably for lots of people, especially the self-portraitures with other men, they’ll think, “This is such a gay work” showing this nude intimacy, which I’m fine with. For people who are more curious, who read my statement and go to the exhibitions to learn a little bit more, I would hope they can understand what I’ve been talking about.

“Inside of My Drawer” (2019). Courtesy of Guanyu Xu and Yancey Richardson Gallery

And in terms of “Temporarily Censored Home,” it’s so complicated in that you need to dig a little deeper to educate yourself about the work. If you’re being too comfortable, then you will only know that it’s a work about this guy subverting his parents home. But once you get a little deeper and know what’s going on with the different images and what’s going on in each image, you will learn a little more. Since the work has already been done, I don’t have much control over what people think. I try my best to push myself, to question myself about how to not create a simple work and to create something that’s layered—something that’s dealing with both history and ongoing events. It’s dealing with different spaces; it’s dealing with personal space but also the political space between the US and China, or even Europe. As an artist, I don’t think I can force any viewer to think a certain way; the work is there and we all have the power to decide if we want to educate ourselves or if we want to learn a little more.

Sandy Chung

Guanyu Xu

Mai Ling

Yancey Richardson Gallery