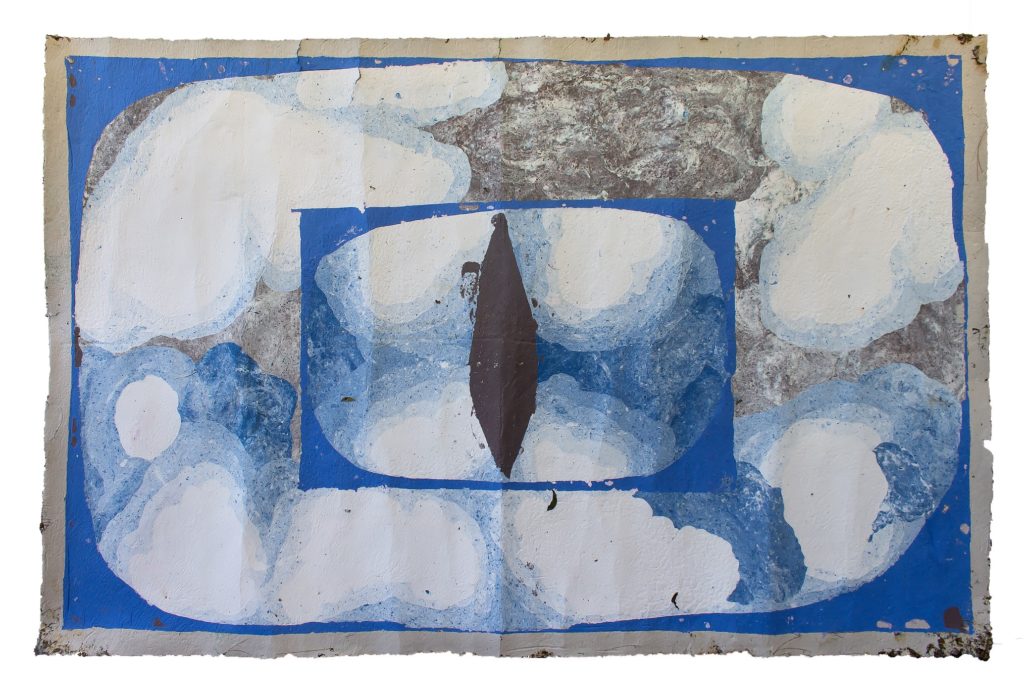

11.5 x 7.5 ft.

Mulberry bark, sun, dust, water, hair, water, fiber-reactive dyes, repurposed paper, and foliage: Sisal Agave and Vetiver

Paper is often treated as mundane: mass-produced and disposable. It is simply a prerequisite for many artists who treat the object as a blank surface upon which to create their artwork. With the proliferation of digital tools, tangible media like paper may even appear obsolete. For multidisciplinary artist Hong Hong, however, paper is the artwork, and the craft of papermaking a site-specific performance piece.

The resulting papers are both works of individual creative expression and practical records of the unique environmental factors allowed to converge at the moment of production. Hong Hong displays a series of works, “The Wet and the Dry: Holding and Grasping,” in a new exhibition curated by Jamillah Hinson and Marissa Del Toro, titled “Let Them Roam Freely” with Darryl DeAngelo Terrell, on display at NXTHVN in New Haven, CT, March 5 – May 15, 2022. FAR NEAR spoke with Hong about papermaking as mapmaking, her approach toward tradition and the journey that led her here.

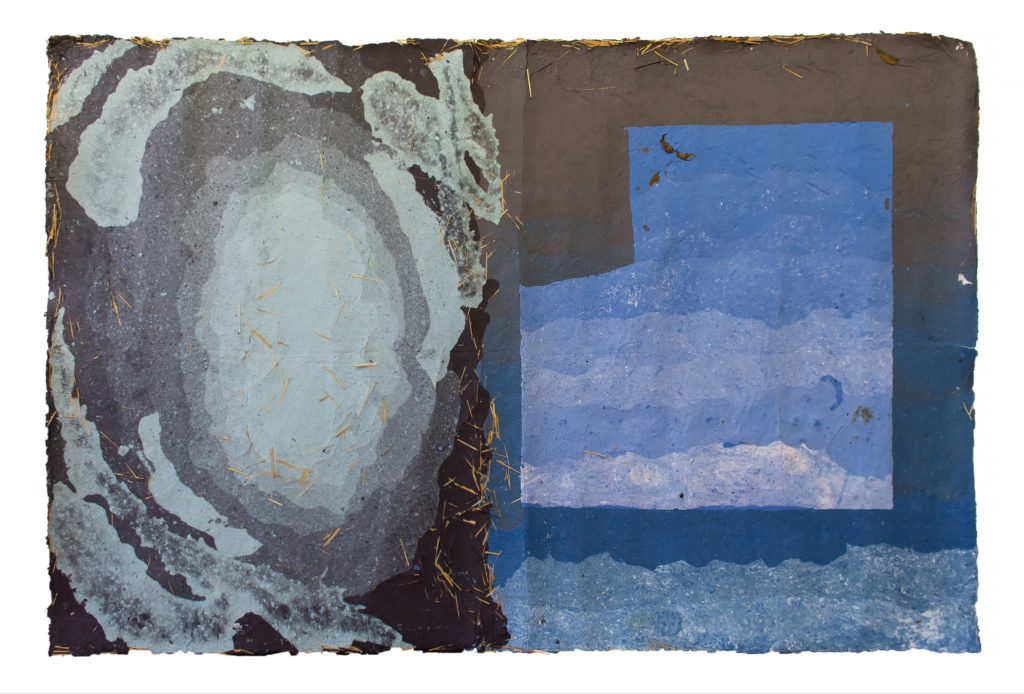

11.5 x 7.5 ft.

Mulberry bark, sun, dust, water, hair, water, fiber-reactive dyes, repurposed paper, and foliage: Sisal Agave and Vetiver

Ariana King How did you begin (and where did you learn) papermaking?

Hong Hong I started making paper at a really tumultuous and uncertain time in my life. My family immigrated to the US in 1999. My parents received their green cards after a six-year wait, which was a scary, grueling, and expensive process. However, I was automatically kicked off of their permanent resident application when I turned 21 in 2010. Despite having lived in the US since I was 10 years old, I would be deported if I didn’t secure a full-time, “legitimate” job or a spot in an academic program immediately after graduating with my BFA.

So I entered the MFA Program with a focus in Drawing and Painting at the University of Georgia in 2011. I was keenly aware that I would have to deal with the USCIS after graduate school ended. Would I have to go back to China? Would I be forced to become an undocumented resident? Within this context, the repetitive analysis of paintings for their formal qualities seemed banal. I didn’t know why I was there, and in a way, I really didn’t want to be there. At the same time, I dreaded graduation. There were all of these desperate feelings inside of me.

In early 2012, I knew that I wouldn’t make another painting ever again. I don’t know why: it was just a sensation that I couldn’t shake. I initially liked being in the papermaking studio because it was on the first floor. Going there meant I would be far away from Drawing and Painting, which was on the third floor. The room was usually quiet, and I was often there alone. I liked being able to hear the sound of water meeting water, as I made paper. In the end, this practice allowed me to remember, revisit and cherish my girlhood and my memories. It was the necessary pivot toward my own history, the histories of my family and the land that I was exiled from. In a way, it was some kind of homecoming.

Mulberry bark, repurposed paper, sun, dust, hair, pollen, fiber-reactive dyes, water, and foliage: Vetiver and Crepe Myrtle

Ariana Why make paper from raw materials at a time when paper is so cheap and readily available?

Hong I like cheap things. I like them because everybody touches, knows and understands them. Cheap things are garbage, and I like garbage. We throw it away. We don’t want to look at or remember the daily wreckage of our own lives. But we somehow keep making more and more of it, day after day, month after month. We can’t stop, even if we wanted to. There is something beautiful about working with the debris and the ruins of our world. Every sheet of paper was once the body of a living tree. Sometimes I forget that.

Ariana Can you speak about the artistic and physical process behind “The Wet and the Dry: Holding and Grasping I and II?”

Hong The birds fly south and then north each year. Like the clouds, they move freely through a borderless expanse. Everything wants to return home. But, unlike the birds, I don’t know where home is or how to get there. Since 2015, I have traveled to faraway locations across the US to create site-responsive, monumental paperworks. I begin each piece by pouring a mixture of pulverized materials and water into a frame that sits beneath the sky. As these substances cure, foliage, debris and insects from the surroundings fall into and become a part of the paper. Passing storms register as ridges and tears on its surface. Each sheet is a photographic still of the time and place it was made: it acts as a geographical and meteorological marker for the voyage of my own body in time and through space. Through the activities of mapping and map-making, I was trying to answer my own questions about homecoming and loss. The pieces in the show were made in three places: Houston (TX), Beverly (MA), and New Haven (CT).

“For me, tradition is about what we have always yearned for. It is about what time, death, and individual circumstance cannot touch, cannot ravage, cannot dilute.”

11.5 x 7.5 ft.

Mulberry bark, repurposed paper, sun, dust, hair, pollen, fiber-reactive dyes, water, and foliage: Vetiver and Crepe Myrtle

Ariana What does tradition mean in the context of your work? Are there any traditional practices that define your craft or traditions you intentionally break?

Hong I grew up in China in the 1990s. My apoor (grandmother) told me when I was young that the sky was the room of some unknown god. I used to go with her to the Buddhist temple to pray. We wrote down our wishes on strips of holy paper that we’d tie to the branches of a tree inside the temple. From these early experiences, I understood paper as a metaphysical, transcendental object, capable of bridging the material with the immaterial.

I also remember reading an essay about the Great Four Inventions when I was in first or second grade. One of those inventions was paper, which dates back to the Han Dynasty. Despite automation and industrialization, this particular process hasn’t changed much. The most important step is the formation of felted fibers into a thin sheet on a mat or some type of screen. Much later, I would revisit and reconstruct this craft through my own practice. I view tradition as a trans-temporal and trans-spatial channel. A group of people, who will never meet each other, were somehow compelled to engage in the same activity, whether it is prayer or making paper.

To me, tradition is one way to dissolve time and distance. It is a bridge between myself and another, as well as between the present moment and an unknowable past. I don’t view it as a set of predetermined parameters, which is why I don’t think about rule-breaking very much. For me, tradition is about what we have always yearned for. It is about what time, death, and individual circumstance cannot touch, cannot ravage, cannot dilute.

11.5 x 7.5 ft.

Mulberry bark, repurposed paper, sun, dust, hair, pollen, fiber-reactive dyes, water, and foliage: Vetiver and Crepe Myrtle

Ariana How do you source ingredients for your pieces?

Hong It’s very organic. In the summer, I go out to the land to harvest mulberry bark as well as foliage from the environment. I also collect paper from my surroundings, since it’s so readily available. I also collect water, dust and debris.

Ariana The Wet and the Dry: Holding and Grasping uses dry materials and blue dyes to evoke water. What do “wet” and “dry” represent?

Hong Wet and dry represent the different states of the materials during the process of hand paper formation. As water evaporates from the gelatinous and wet mixture of bark, repurposed paper and pigment, it cures and transitions into a flexible, cohesive surface. They also reference our experiences of seasons and climates, as well as the complicated ways these fluctuations are internalized and carried within our bodies as knowledge. When I was working on this project at NXTHVN, I had just finished a book that means a lot to me –– “Indexcards” by Moyra Davey. There was a chapter in it titled The Wet and the Dry. Finishing the book opened a void: I knew I wouldn’t be able to encounter it for the first time again. It was simultaneously inside of me and behind me. I simply wanted to pay homage to its significance to me.

Ariana How does your work reflect your own voyage, both throughout the course of your life and specific to the locations your work brings you?

Hong I’m very interested in Chinese folklore. I think folklore, at its most essential, is about cosmological order. If the universe is a series of concentric circles that reverberate from each other, where do we belong within that system or whole? Again, this goes back to the idea of mapping. And what is a myth if not a map? Every story is a diagrammatic representation of where we come from and where we will one day go. I talked about each sheet of paper as a geographical and meteorological marker for the voyage of my body in time and through space. I think the projects are just that: a catalog of locations and a reconstitution of where I have been. I lost my body when I came to America. To put it a different way: when I was 10 years old, I lost my body. So, all work is really the same work. All work is a search for a body: mine. All work is an attempt to recreate, rebuild and reclaim a body: my own.

Born in 1989 in Hefei, Anhui, China, Hong Hong earned her BFA from State University of New York at Potsdam (2011) and MFA from University of Georgia (2014). Since 2015, she has traveled to faraway locations across the US to create site-responsive, monumental paperworks. In this nomadic practice, traditional methods of Chinese papermaking coalesces with painting, monastic rituals and feminist performances. These works have been included in exhibitions at Ringling Museum of Art, Real Art Ways, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Georgia Museum of Art, Penland School of Crafts, Artspace New Haven, Lawndale Art Center and Jewett Art Center, among others. Hong is the recipient of grants and fellowships at NEA (2019), FCA (2015, 2020), MacDowell (2020), Yaddo (2019), McColl Center for Art and Innovation (2022), Vermont Studio Center (2019), I-Park (2019) and Houston Center for Contemporary Craft (2020 – 2021). Hong currently lives and works in Massachusetts.

Courtesy of the artist: Hong Hong.