Few outside Taiwan are aware that the island is the homeland of Austronesian people. Over 4,200 years ago, their ancestors began migrating from Taiwan to places like the Philippines, Easter Island, and New Zealand. Like many Indigenous populations, Indigenous Taiwanese have long faced discrimination. They were labeled as “Eastern Savages” (東番) in the Ming Dynasty, and 生番 (“raw, wild, or uncivilized”) or 熟番 (“cooked or tamed”) in the Qing dynasty, depending on whether or not they submitted to the ruling class.

Colonial powers deepened their struggles. The Dutch and Spanish took land and imposed Christianity in the 17th century. From the 18th to 20th centuries, more land was lost to Chinese and Japanese rule through force or fraud. Under Japanese occupation (1895–1945), many were displaced, pressured to adopt Japanese customs, and forced into model villages. After 1945, the Kuomintang regime imposed Mandarin and Han Chinese culture, pushing Indigenous people out of the mountains and into cities. Industrialization in the late 20th century led to further displacement and discrimination. Today, at least 10 of Taiwan’s 26 Indigenous languages are extinct.

Amid this history of subjugation, many Indigenous artists and activists are actively reclaiming their personal and communal histories. Misafafahiyan Metamorphosis, a work by Amis artist Posak Jodian, centers on Hao Hao, a 70-year-old Amis performer from Fata’an, an Amis tribal village in Taiwan. Styled like karaoke backing tracks, the piece weaves together music and sounds from Hao Hao’s daily life with dialogue, costume changes and humor. Throughout the film, Hao Hao performs a range of Amis songs that explore themes of familial love, the emotions of returning home and nightlife culture.

After decades of invisibility, Posak Jodian’s film and Hao Hao’s performances aim to bring the labor experiences and displacement of Taiwan’s Indigenous people into contemporary art. Their work creates a nuanced portrait of Indigenous resilience, highlighting survival through cultural self-assembly and resistance through gender fluidity.

Below, FAR–NEAR speaks with Posak Jodian about her relationship with Hao Hao, her inspiration for the film and her hopes for the future of Amis culture.

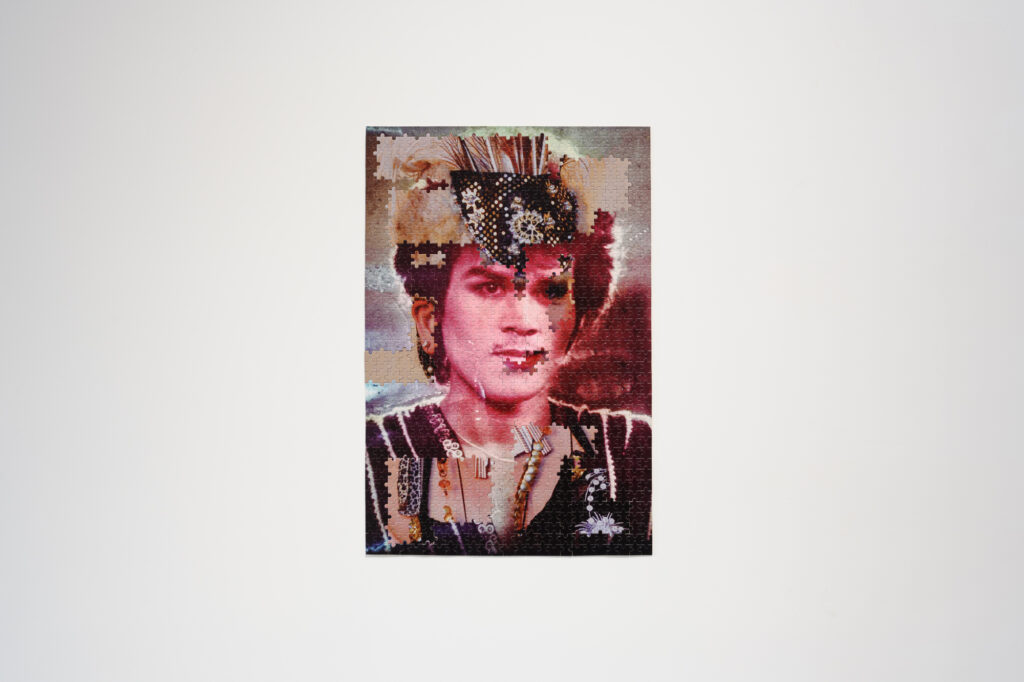

Still from Misafafahiyan Metamorphosis

Lulu Yao Gioiello Can you tell me about your relationship to Hao Hao? How did you meet? How did you end up filming this series together?

能跟我聊聊你和皓皓的關係嗎?你們是怎麼認識的?最後又是如何一起拍攝這個系列的?

Posak Jodian Hao Hao is a well-known person in my village. When I was younger, I often saw her performing on stage at weddings and celebrations in our community. Her performances are deeply woven into our collective memory of village gatherings and everyday life. Later, I discovered that she was a good friend of my father. They are of a similar age and often met up while working away from home in Taipei. It was through my father that I gradually got to know Hao Hao better.

She first appeared in my work in 2018, in my video series Lakec (Crossing the River). That project explored ethnic identity in relation to rivers and landscapes, reflecting not only my home, the Fata’an community, but also the experiences of Indigenous people living in urban areas along rivers. In Lakec, Hao Hao briefly appeared in a few shots as an urban Indigenous figure.

Through that initial collaboration, she began to understand my work and artistic approach, which helped establish a sense of trust in the filmmaking process. At the same time, my artistic focus shifted — from exploring identity through land, mythology and history in Lakec to investigating the boundaries of cultural identity through Hao Hao’s life experiences and gender-fluid performances.

皓皓在我的部落裡是一個知名的人物,我年輕時就時常在部落裡的婚宴喜慶上看到她在舞台上表演,她的表演可以說是我們對部落聚會的記憶與日常的一部分。後來我發現她是我父親的好朋友,他們年齡相仿,過去離鄉在台北工作時也時常會聚會,所以我是透過父親才漸漸跟皓皓變得熟識。

她其實最早出現在我的作品當中,是在2018我的系列作品Lakec(渡河)的錄像作品裡,Lakec主要是探討族群認同與河流、地域的記憶與關係,影片的內容不僅僅關於我的故鄉馬太鞍部落,也是關於在都市裡靠著河岸生活的都市原住民,所以皓皓當時是以都市原住民的形象匆匆的出現幾個鏡頭。

由於前作Lakec的接觸,皓皓開始理解我正在做的事情與工作的方法,也才慢慢建立起一種拍攝上的信任感。而我也從Lakec對土地、神話歷史的族群認同探索,轉向透過皓皓的生命經驗與跨越性別邊界的表演來探索關於族群文化認同的邊界。

Lulu How long did it take to shoot this film?

這支影片的拍攝花了多長時間?

Posak The actual filming process, from the moment I clearly defined the project and began shooting intensively, took about three months. However, before that, we had already known each other for some time. There were many moments when we weren’t working at all — just spending time together, chatting, singing karaoke and having fun. She also became good friends with my cinematographer, lighting designer, producer and other crew members. Through this process, we also met many other performers who are engaged in similar forms of performance.

我真正開始明確的執行計畫並且密切的開始拍攝的工作大概是3個月左右的時間。但是在那之前我們已經認識彼此一段時間,並且我有很多時間我們是沒有在工作,僅僅是日常的聊天或是唱卡拉ok玩樂在一起,她與我的攝影師、燈光師與製片等工作人員也都變成了好朋友,我們也因此結識了許多也從事同樣表演的表演者。

Lulu What were some goals you and Hao Hao had for the video?

你和皓皓對這支影片有什麼目標?

Posak First, I wanted this work to bring awareness to performers like Hao Hao — artists whose experiences and performances are deeply intertwined with Taiwan’s Indigenous communities, society and history.

Beyond that, I see Hao Hao’s performances as playful and full of vitality. Her self-presentation is a clever subversion of the gaze of others, actively manipulating audience perceptions — both on and off stage — of gender and Indigenous identity. Through the reassembly of moving images, songs and photographs, we aimed to highlight the technical artistry and aesthetics within her performances. Her work carries both historical depth and lived experience, embodying the magical moments of community stage performances while also being an essential part of our collective memory and everyday life.

我想首先是能夠透過這個作品知道有像皓皓一樣的表演者,他們所經歷過的表演與經驗,是與原住民與台灣的社會、歷史息息相關的。

再來,皓皓的表演對我來說玩味性十足,是一種充滿活力、玩弄著他者凝視的自我呈現,表演中操弄著舞台上與舞台下觀眾對性別、原住民族群的印象與框架。透過動態影像、歌曲與照片的重新拼貼與組成,我們想要呈現在這個表演中的技術與美感,它所承接的歷史與經驗是部落的舞台上所呈現的魔幻片刻同時也是我們記憶日常的一部分。

Still from Misafafahiyan Metamorphosis

“These Amis-language songs are not ancient tunes passed down from our ancestors, nor are they traditional work songs or folk melodies from the village. Instead, many of them were created and circulated between the 1970s and 1990s, during a time when many Indigenous people left their hometowns to work in the cities. These songs often depict the struggles of working away from home, the pain of separation from family and loved ones, and the sense of alienation when returning to one’s hometown after years away.”

Lulu Can you give a bit more context about the songs Hao Hao is singing?

你能多介紹一些皓皓演唱的歌曲背景嗎?

Posak In Hao Hao’s house, there has always been a piece of paper filled with handwritten song titles and corresponding karaoke machine numbers — her go-to setlist for performances. From this list, I selected three songs for the film: 親情 (Kinship), 來自異鄉的朋友 (A Friend from Elsewhere) and 午夜的霓虹燈 (Midnight Neon Lights).

The songs on Hao Hao’s list were already quite unique. These Amis-language songs are not ancient tunes passed down from our ancestors, nor are they traditional work songs or folk melodies from the village. Instead, many of them were created and circulated between the 1970s and 1990s, during a time when many Indigenous people left their hometowns to work in the cities. These songs often depict the struggles of working away from home, the pain of separation from family and loved ones and the sense of alienation when returning to one’s hometown after years away.

Another interesting aspect of these songs is their fluidity. The original composers are often difficult to trace, and as the songs were passed down over time and across different places, multiple versions emerged. Eventually, they were quietly recorded and archived into karaoke systems, where they became fixed in a particular form.

In Amis tradition, songs take on different forms — there are ritual songs performed only in ceremonies, ancient tunes passed down through generations, work songs sung during farming and improvisational folk songs woven into everyday life. Often, elders will modify lyrics based on their personal experiences or the moment they are singing. In this way, songs continuously document history, carrying the voices and experiences of different generations.

For the film, I wanted to use these three songs to represent different stages of Hao Hao’s life.親情 (Kinship) reflects the farewell to family and the beginning of a life working away from home. 來自異鄉的朋友 (A Friend from Elsewhere) conveys a growing sense of estrangement from her hometown, but also marks the moment she begins to assert her own identity. 午夜的霓虹燈 (Midnight Neon Lights) paints a vivid picture of nightlife and the ambiguous emotions shared among friends.

Additionally, I wanted to embrace the evolving nature of these songs. Just as they have been reshaped through time and space, we created new arrangements and remixes of these three tracks, crafting a contemporary version that belongs to Hao Hao.

皓皓家的桌上長期壓著一張紙,上面滿滿寫著他平常表演時會表演的曲目及歌曲在卡拉ok點唱機裡的號碼。我在他平常表演的曲目中挑選了三首歌曲,分別是「親情」、「來自異鄉的朋友」,以及「午夜的霓虹燈」。

那張紙上,皓皓本來挑選的曲目就很特別,這些阿美族語歌,它們不是祖先所留傳下來的古調、也不是部落裡的工作歌或生活歌謠,這些歌曲許多是在早期七十至九十年代,族人離開家鄉在城市裡工作時所被創作出來與流傳的,這樣的歌曲時常描寫著離鄉工作的情境與環境、與家鄉和親人、愛人的離別與想念,還有再次回到故鄉的疏離與陌生。

另外,這些歌曲還有一個特徵,它們最初的詞曲創作者往往已經很難在追朔,歌曲隨著時間、地點的流傳也會出現不同的版本,最終它們被悄悄地灌錄進卡拉ok的系統裡有了一個特定的版本。

在我們阿美族的傳統裡,歌曲有不同的形式,有儀式才會演唱的祭歌、祖先流傳下來的古調、務農工作時的工作歌,以及生活中會即興演唱的生活歌謠,有的時候一個同樣的曲調,老人家在演唱時也會隨著當下工作的狀態、自己的生命經驗等來重新編改歌詞。歌曲就像書寫著歷史一樣,不斷傳唱著不同人的歷史與經驗。

所以,在影片的架構中,我也想要試著透過三首不同的歌曲來帶出皓皓的生命裡的不同階段,「親情」是與家人的離別,離開家鄉工作的開始與歷程,「來自異鄉的朋友」透露著與家鄉的關係產生疏離但她也同時開始展現自己,「午夜的霓虹燈」歌詞裡講述著夜生活的情景以及與朋友間的曖昧情愫。並且,我想沿用歌曲持續傳播改編的概念,這三首歌曲我們也重新的作編曲混音,創作出屬於皓皓的當代版本。

Lulu How common is it to be accepted as queer or trans in Amis culture?

在阿美族文化中,酷兒或跨性別者被接受的情況有多普遍?

Posak It’s complex, under the influence of colonization and Christianity, today discussing queer and transgender issues within Indigenous communities can often be challenging.

When I processed and approached this project, I decided not to attempt to define or analyze Hao Hao’s sexual orientation. I felt that aligning our perspectives on gender would be difficult — perhaps even unnecessary. Even though we come from the same village and culture, the generational gap and the different social environments we grew up in have shaped our understandings of queerness and trans identity in distinct ways.

From our conversations, my interpretation of Hao Hao’s perspective is that she does not see herself through the contemporary labels of gay, straight, or queer, as younger generations might. Instead, she and other performers like her recognize themselves within a self-defined community — what she describes simply as “people like me.”

這個問題有一點複雜,在殖民與基督宗教的影響下,普遍上來說當我們試圖要在部落中談論酷兒與跨性別的議題時,時常是相對困難的。

在我創作的過程中與內容上,我並沒有往試圖推敲皓皓的性向的方向走去,我想對她來說要理解並且在我與她之間對齊對於性別的想法是很難達到的。縱使我們都是來自同一個部落,但是由於世代的差距,來自不同時代與環境的影響,我們之間對酷兒或是跨性別的認定也會產生不同的分歧。從我與她對話的過程中,我對她所表達的話的理解是,她不覺得自己是現在年輕世代口中的同性戀者、異性戀者或是酷兒,她與和她一樣類型的表演者們是一個她們所互相認定的「像我一樣的人」的群體。

Lulu Like Hao Hao, there are Amis people who left their hometowns to make a living through performance during the 島内移工 (interisland migration) but eventually returned to their hometowns. In what ways do you think this kind of migration brought about a new form of queer culture to tribal communities? Did this kind of migration and return bring about other forms of culture or identity that weren’t a part of the Amis community before?

像浩浩一樣,有些阿美族人曾在島內移工的浪潮中離開家鄉,透過表演謀生,最終又選擇回到部落。你認為這樣的遷徙如何為部落社群帶來了一種新的酷兒文化?這樣的遷徙與回歸是否也引入了其他原本不屬於阿美族社群的文化或身份認同?

Posak This style of performance is not what we traditionally recognize as Amis culture. Many performers like Hao Hao have gained experience in different cities and even abroad. Hao Hao herself received professional vocal training in the city and was part of a military performance troupe during her service. Because of this, their performances have evolved alongside Taiwan’s shifting political and economic landscape, adapting through multiple layers of colonial influence. Today, their performances incorporate a variety of cross-cultural elements, yet their primary audience has become their own Indigenous communities.

In the village, the performances that Hao Hao and her peers have brought back have become an ingrained part of our collective memory and daily life. Their audience is not a niche group but rather an everyday crowd — wedding guests, community members, people of all genders, sexualities and ages. Because of this, I believe that Hao Hao’s stage does more than entertain; it subtly challenges and reshapes people’s preconceived notions of gender. Over time, this form of expression has become an accepted and natural part of our contemporary Indigenous experience.

這樣的表演並非我們所認知的傳統阿美族文化,像皓皓這樣的表演者許多都有在不同城市、國家的表演經驗,甚至像是皓皓本身是在城市裡面受過專業的歌唱訓練、也在服兵役的期間加入軍中的表演團體,也正是因為這樣她們的表演歷程隨著台灣整體社會的政治、經濟轉變,在多重殖民的環境中,她們的表演也經歷過不同的轉變。如今,她們的表演融合了許多異文化的元素,但是她們觀眾大多變成是自己的原住民族人。

在部落中,皓皓與她的同行們所帶來的表演已經變成我們記憶中日常的一部分,她所面對的觀眾是部落中非常普遍的不特定群眾,是會參加婚宴喜慶不同性別、性向、年紀的眾人們。所以我認為透過皓皓的舞台與表演,舞台下的觀眾在這樣的表演中也無形中翻轉著自己對性別的既定框架,並且它早已被接納成我們當代日常的一部分。

Still from Misafafahiyan Metamorphosis

Lulu Do you have any future plans to make more films with Hao Hao?

你未來有計畫再與浩浩合作拍攝更多影片嗎?

Posak This project is still ongoing and expanding. It is gradually extending to include different performers and their unique performance styles, exploring the histories they have experienced, the types of performances they engage in, and the intersections and tensions between their art and their ethnic identities. And since my artistic practice is primarily rooted in visual arts, the project will continue to be presented mainly through exhibitions.

這是一個仍然在持續並且擴展中的計畫,它漸漸地走向擴延至不同的表演者以及她們的表演風格上,關於她們所經歷過的表演歷史、所操演的表演類型,與族群身份的交會與張力。

由於我自己的創作方向比較是朝著視覺藝術的路徑發展,因此目前的計畫還是會以展覽的呈現為主要的呈現方式。

Lulu What are your hopes for the future of Amis culture and the community?

你對阿美族文化和社群的未來有什麼樣的期望?

Posak As an Indigenous artist, I see in Hao Hao and performers like her a powerful vitality in how they interpret their gender, ethnicity, and identity. To me, they are not just resisting rigid, traditional, or binary frameworks of identity—they are also actively responding to and reshaping mainstream values. Their performances play with and subvert society’s established norms and expectations.

I hope to convey this rich, multidimensional vitality through my work. While their performances may not fit within traditional Amis artistic expressions or mainstream gender norms, their experiences reflect Taiwan’s larger history—the martial law era, societal discrimination, and the gaze of otherness. Yet, through these performances, we have an opportunity to reconsider and redefine our own understanding of gender, identity, and culture.

作為一個原住民身份的創作者,我在皓皓以及與她同類型表演的表演者身上,感受到一種詮釋自己性別、族群,以及身份認同的強烈生命力,對我來說她們不僅僅只是單純的對抗傳統的、樣板化的、單一與二元的身份框架,也同時對這些主流的價值做了回應與推移,像是以這些表演來玩弄社會裡既定的價值觀與想像一般。

我自己很希望能把這樣立體的,有厚度的生命力傳達出來。她們也許做的不是傳統的表演,也不是符合主流社會性別價值觀的表演,在她們的經歷中可以看見她們走過台灣的戒嚴時期,被社會歧視、承受被異化的眼光,但那其實同時也是我們所走過的歷史,我們其實可以藉由他們的表演重新思考與看待自己的性別、身份與文化。

Misafafahiyan Metamorphosis will be screening at FAR-NEAR on October 4th, followed by a participatory conversation and workshop on cultural preservation and regeneration in response to the film.

Posak Jodian is an Amis artist living in Taipei with a background in ethnolinguistics and communication studies. Using video as method, and ethnic identity as a starting point, she observes traditional tribal field formulation and the urban life of Indigenous people who left their hometown. Using ethnic and cultural action as a fulcrum to open the boundaries between identity and recognition, she participates in various mass and youth movements at the in between of cities. She is a member of OCAC, Halfway Cafe and Taiwan Haibizi Tent Theatre.

Lulu Yao Gioiello